2008 was a big year for adults with ADHD. For the first time health authorities in England recognised adult ADHD and guidelines were published by NICE. Whilst medication was recommended as a first line treatment, even back then the experts understood that it wasn’t enough.

“Psychological support should be available, targeted at the particular problems related to ADHD. This includes a wide range of treatments and could include psychoeducation, anger management, daily living skills and treatment of comorbid anxiety and depression…..Adults starting on pharmacological treatment for the first time will often need advice on how best to take advantage of potential improvements in their mental state and level of functioning. ADHD coaching or long-term support will be important in some cases where short-term psychological interventions are insufficient.”

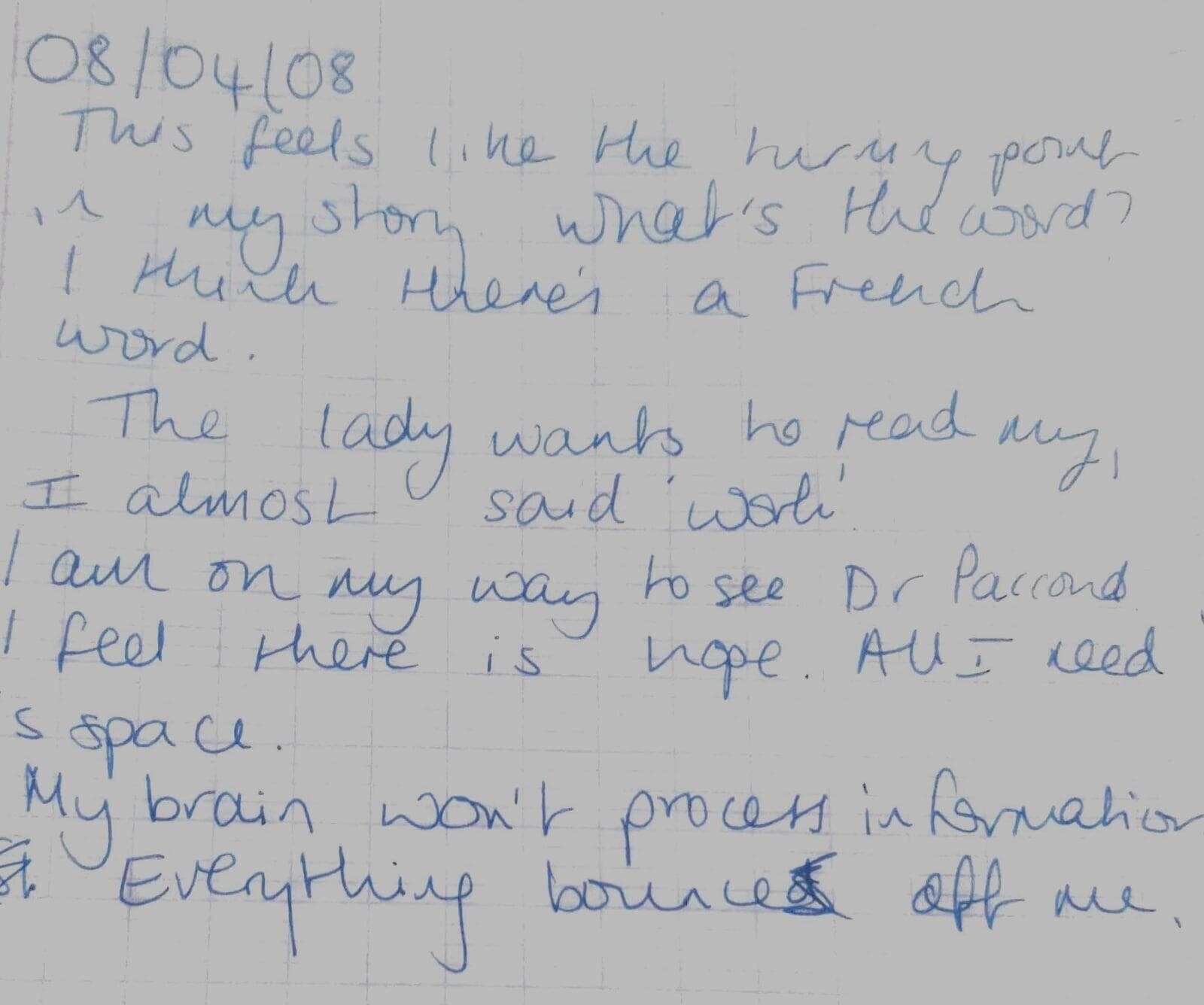

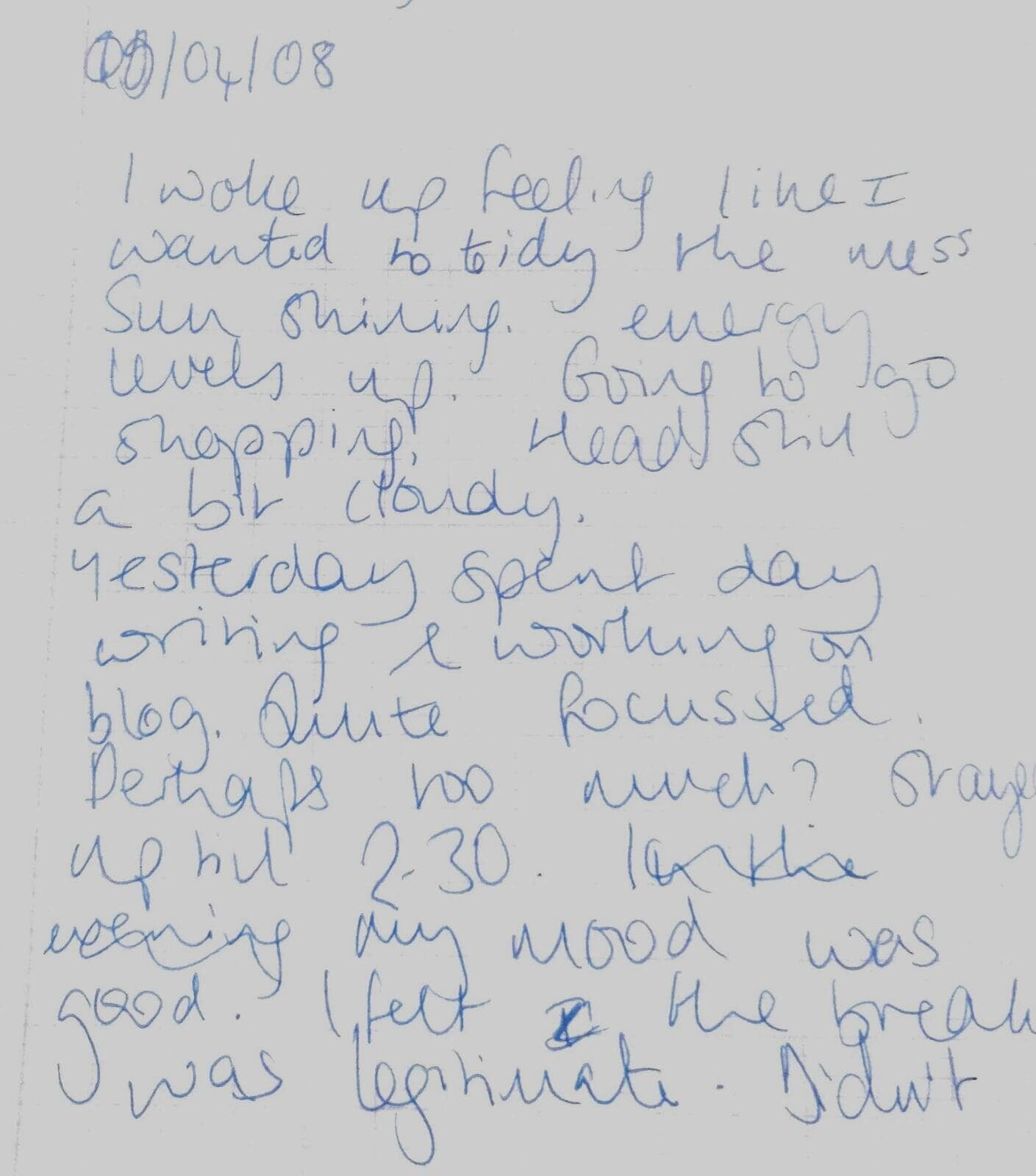

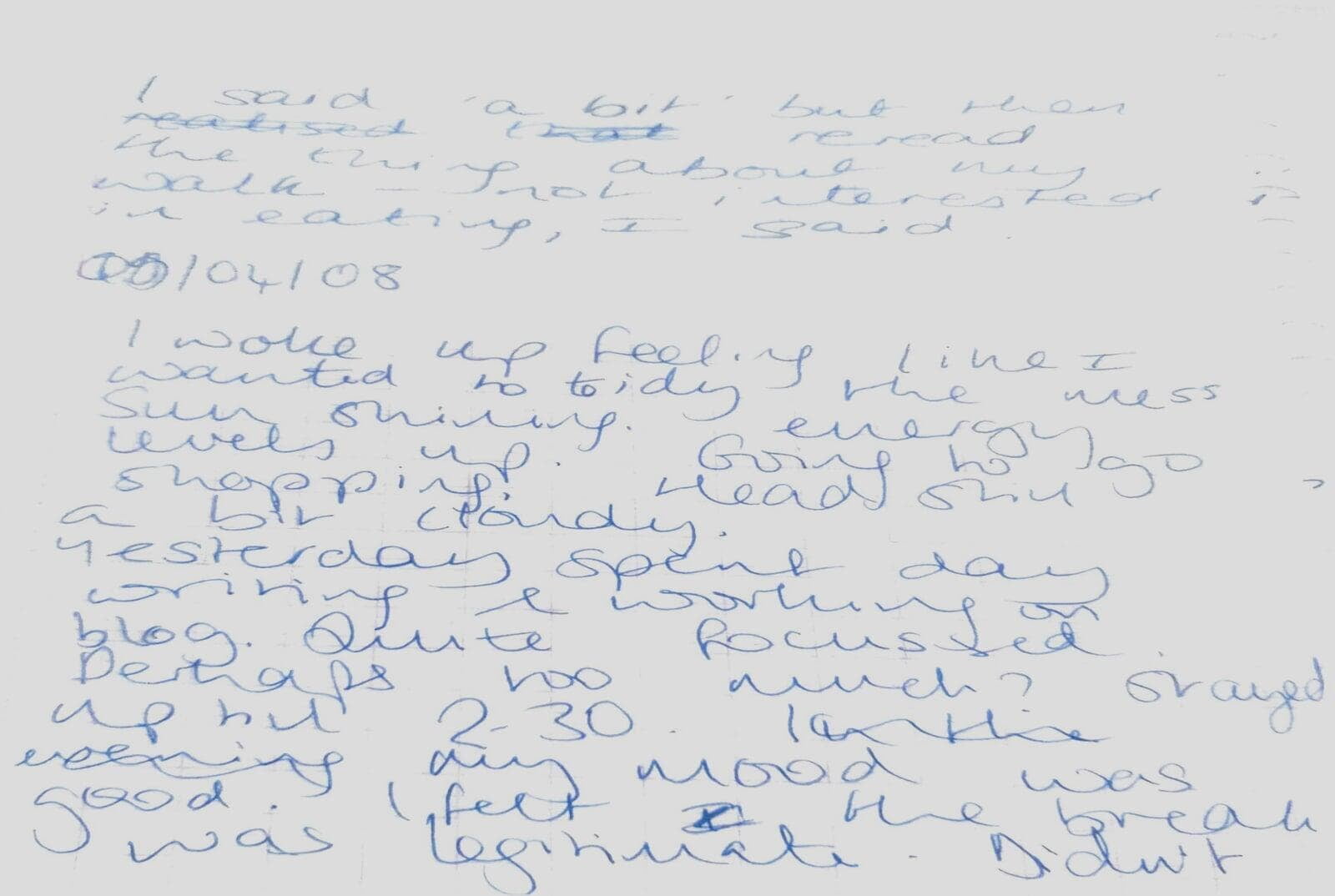

On the other side of the Channel, 2008 was a big year for me too. In April of that year I saw a psychiatrist for the first time and was signed off work for 3 months. I had been struggling with my mood for a while but over a period of months things had got worse. I was experiencing dizzy spells and finding the crowds and noise of Paris increasingly difficult to deal with. I found myself incapable of making even the simplest decisions and would find myself frozen to the spot in the supermarket trying to decide what to buy for dinner. Despite having little to do at work I was overwhelmed and burnt out.

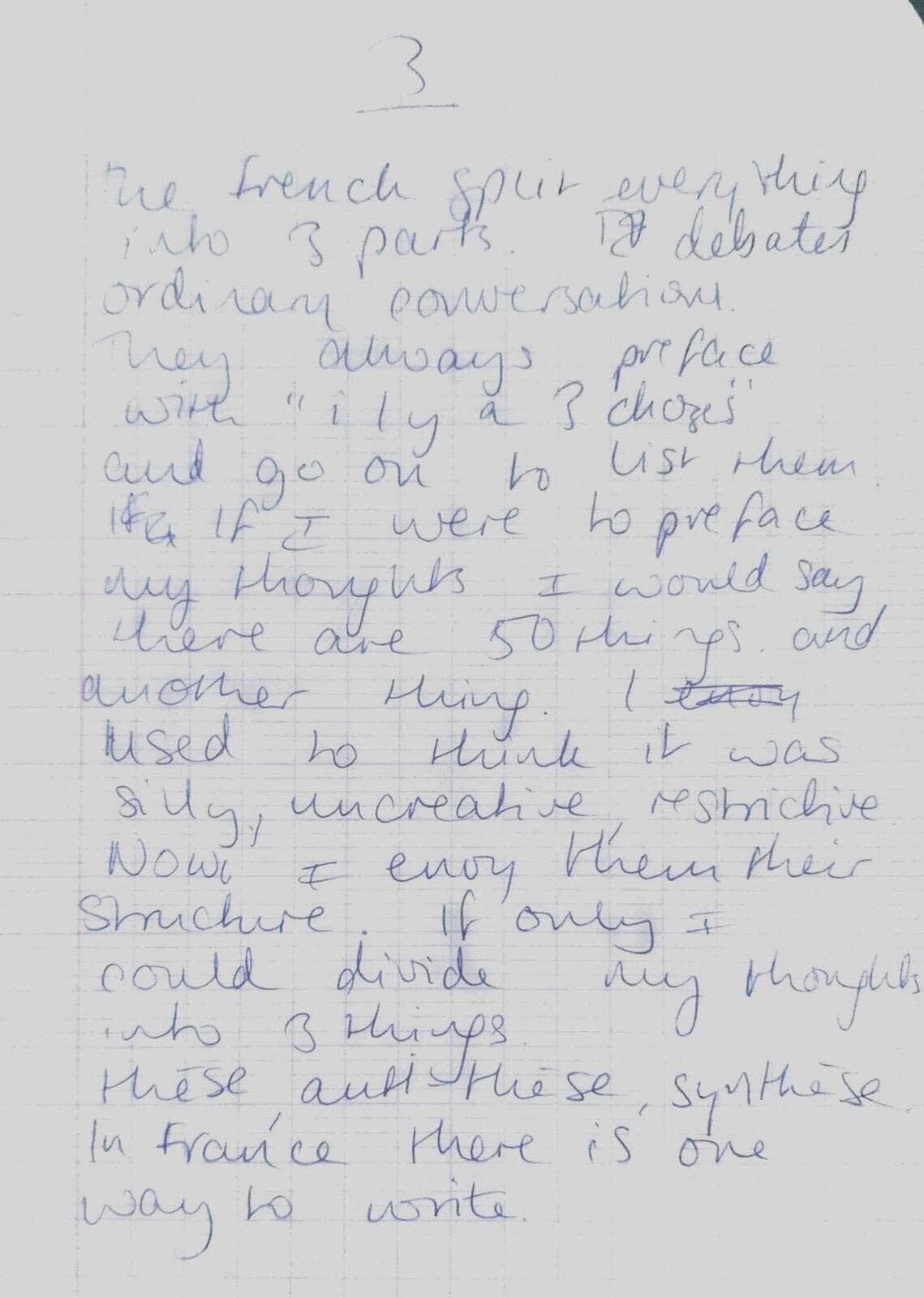

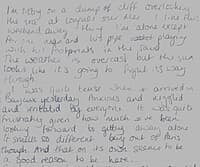

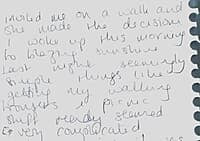

For years my brain had been filled with turmoil, trying to figure out what to do with my life and what my purpose was. I would constantly hit “refresh” on my browser in an attempt to scratch an invisible itch, gaze up at the buildings in the industrial park I passed on the way to work, wistfully wondering if somewhere inside there was a job I could do. I made impulsive decisions that filled me with shame and self-hatred and regularly spent days binging episodes of Friends to avoid confronting the world. I hated the sunshine because I reminded me that I was wasting my life. In an attempt to give my life meaning and purpose I had impulsively decided to walk hundreds of miles across France and write a book about it. I had become obsessed with the project to the exclusion of everything and everyone else but it had become so large in scope that my brain couldn’t keep hold of it any more and I began to unravel.

I’d been seeing a clinical psychologist (I called “the lady”) for 5 years but never seemed to make any progress. I could never remember situations or feelings, or even remember what we had discussed the previous week. Therapy had become just another thing I couldn’t do, another stick to beat myself with. One day I woke up and just couldn’t get out of bed. My therapist finally admitted defeat referred me to a psychiatrist who signed me off work.

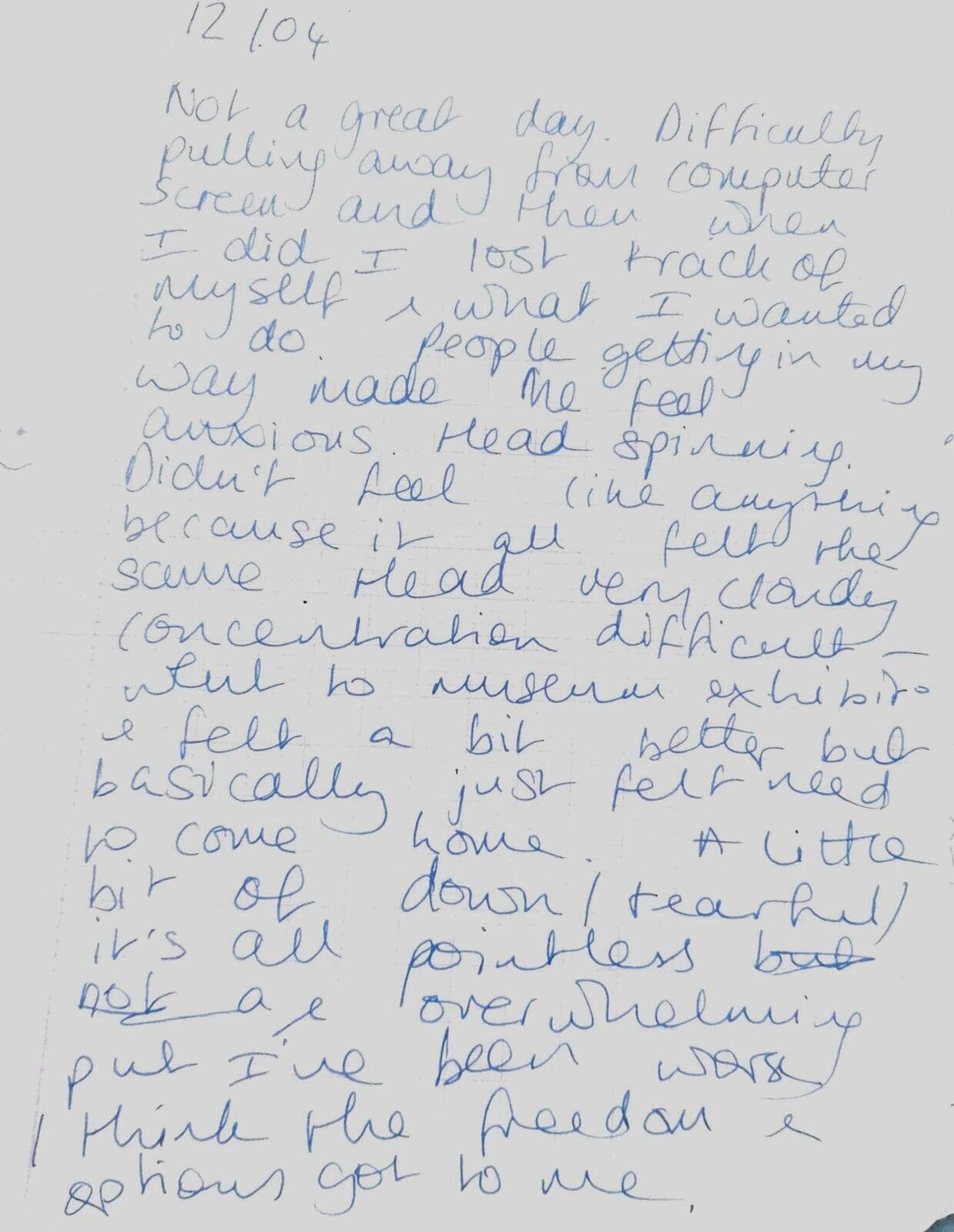

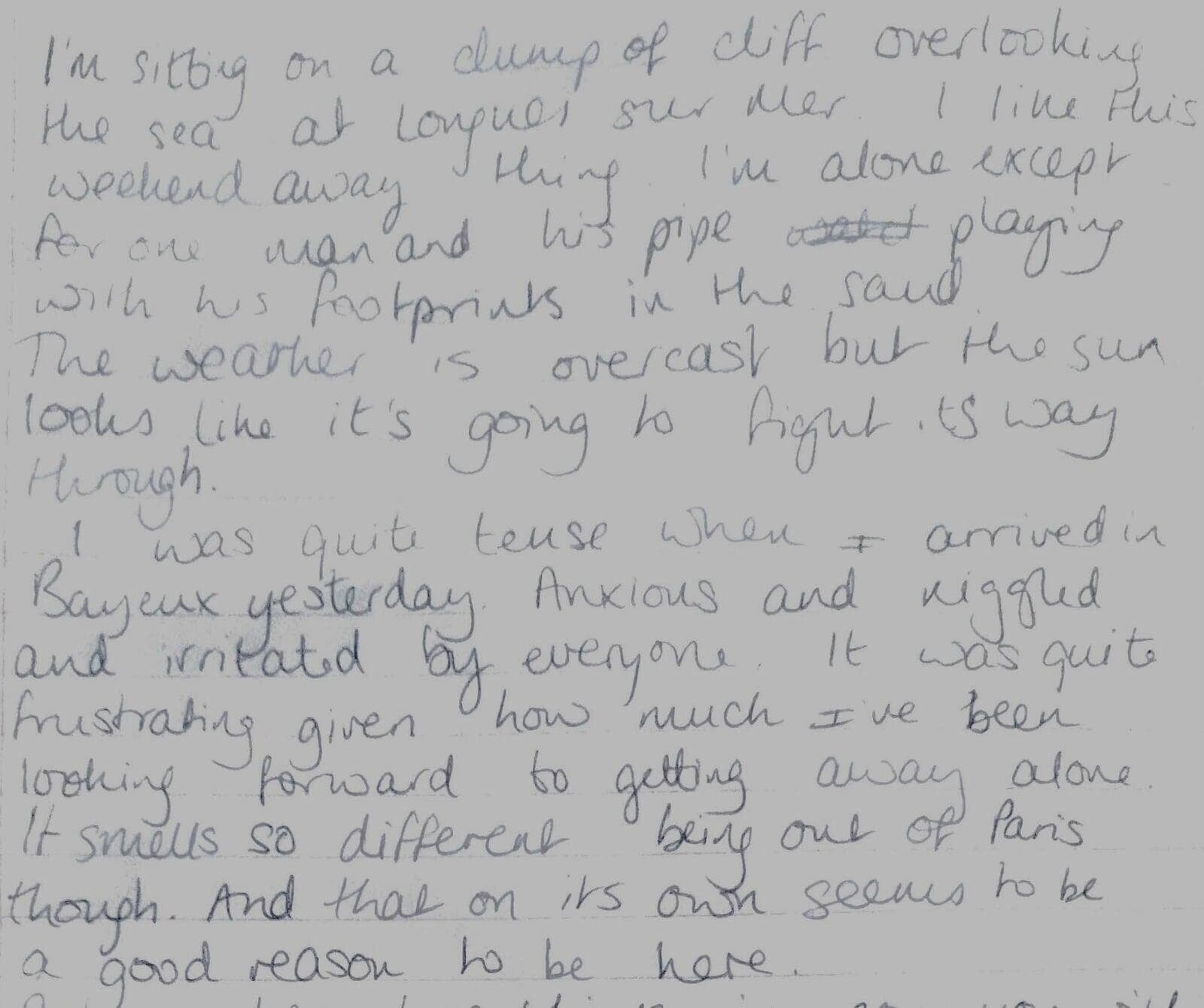

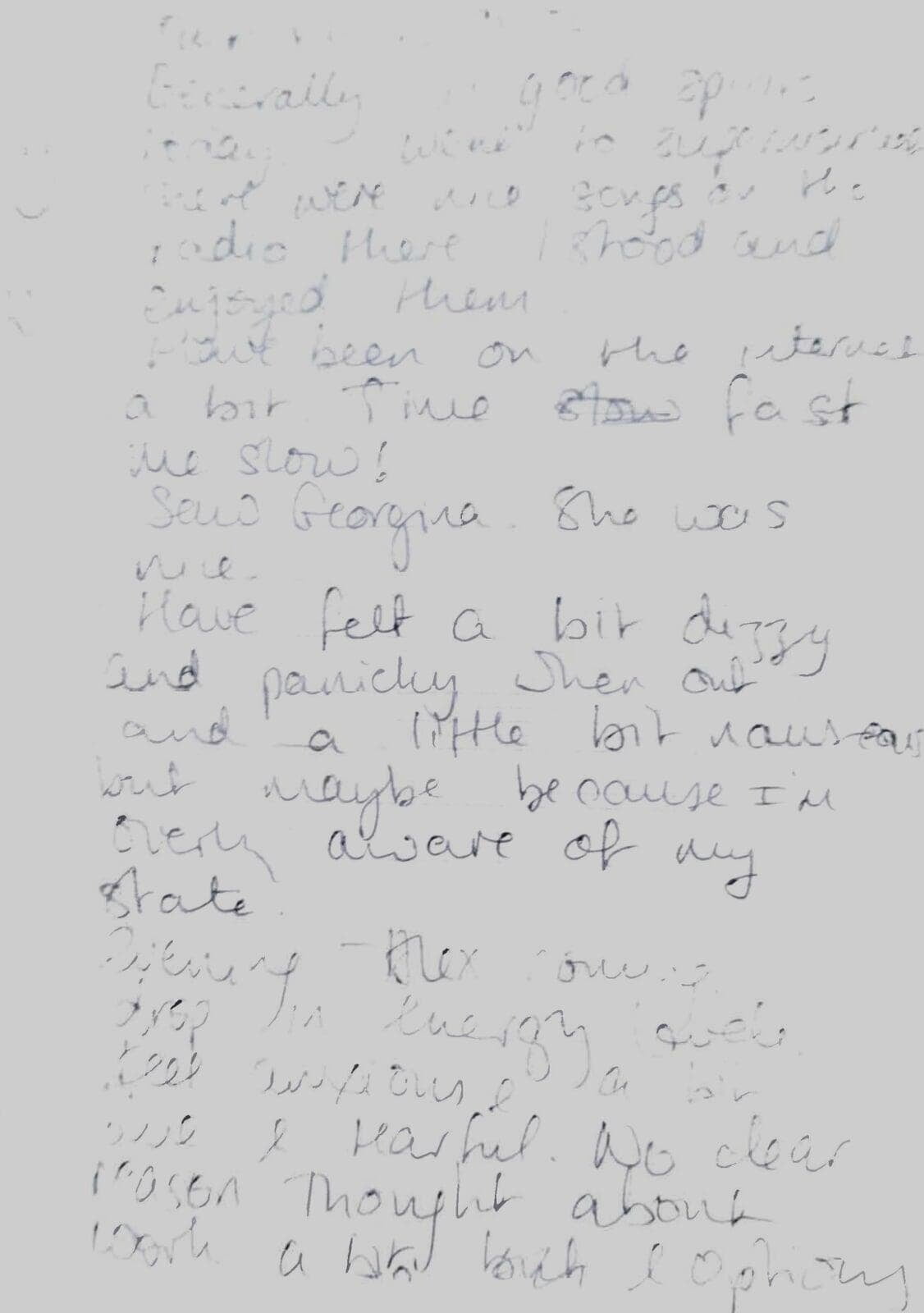

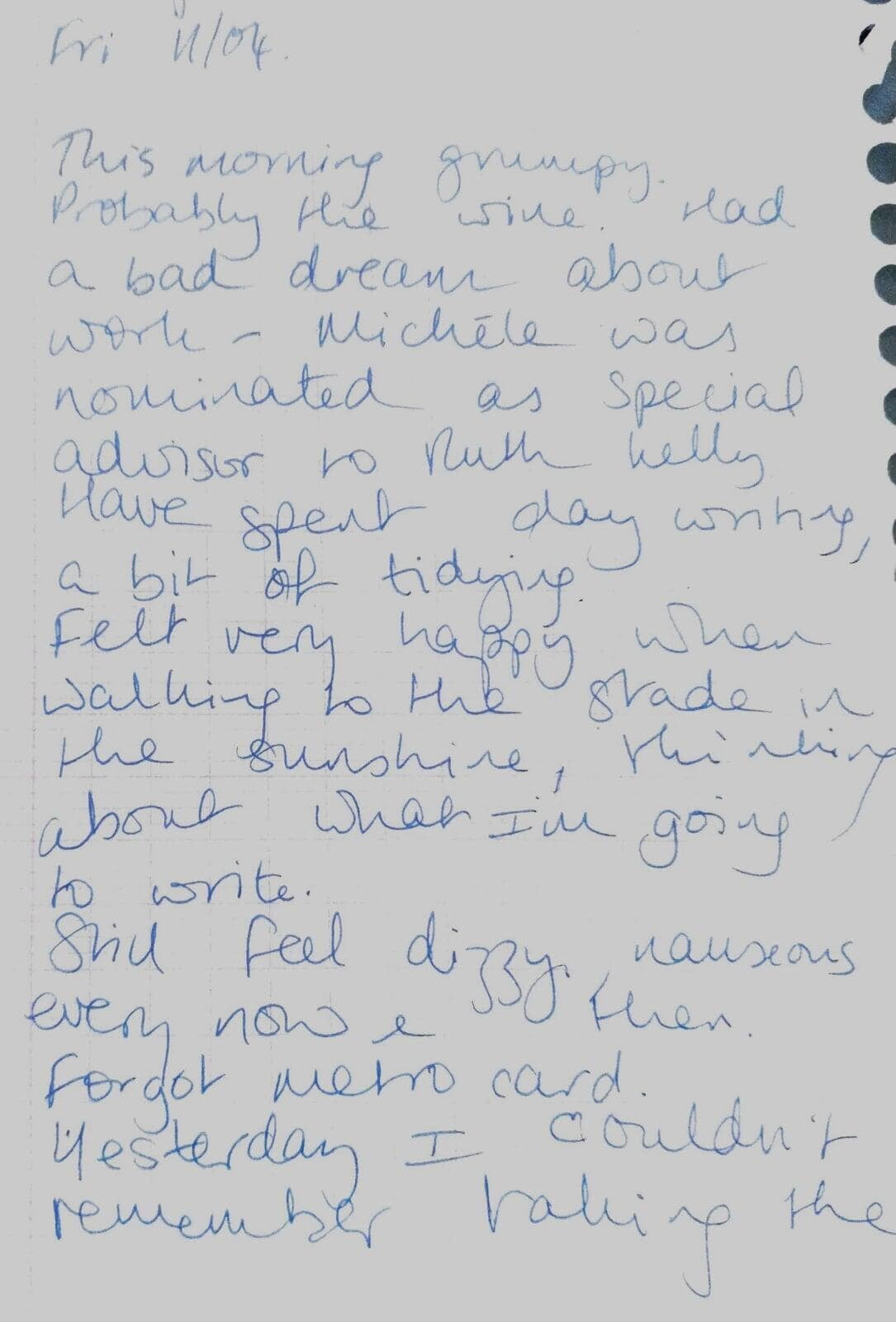

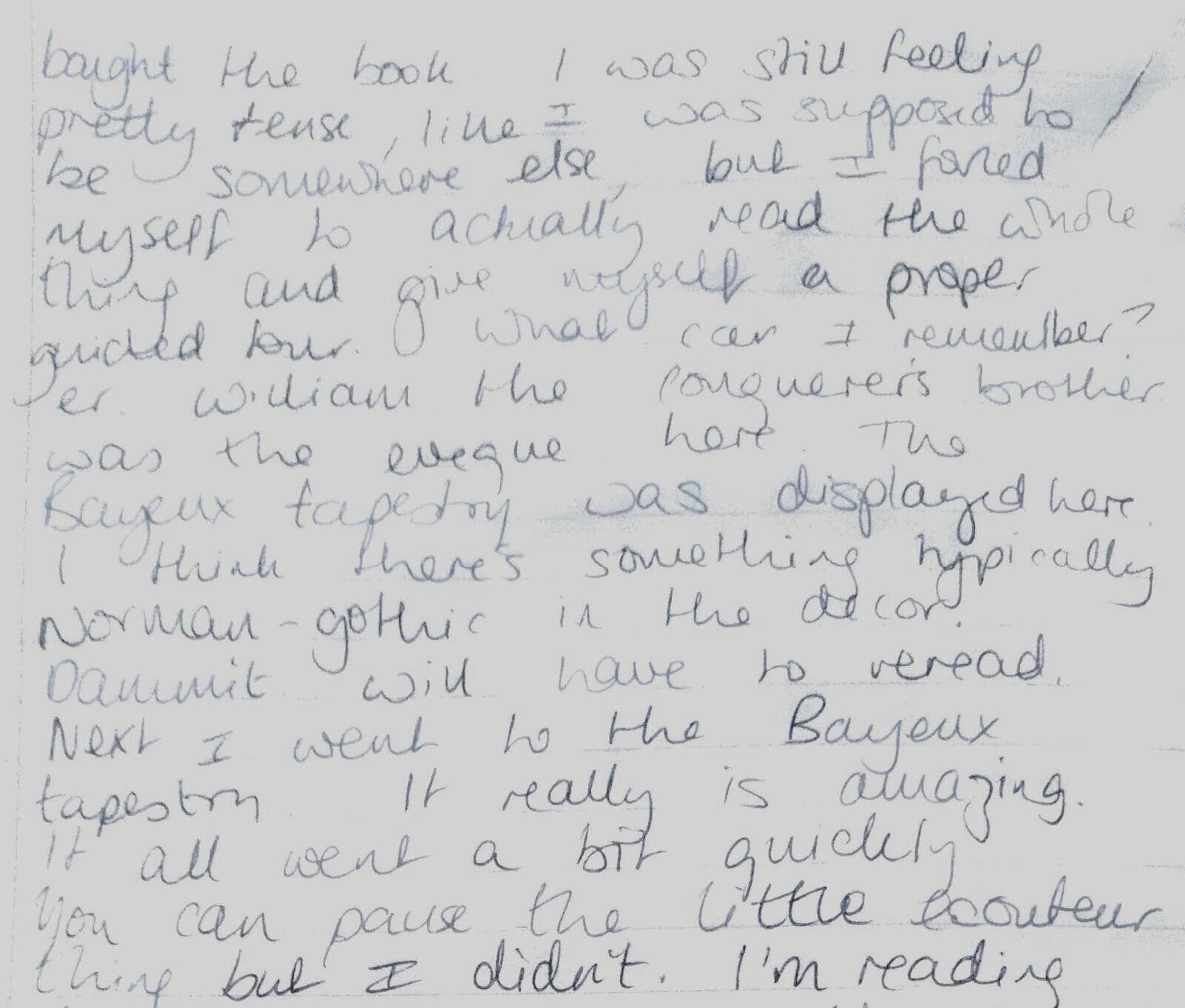

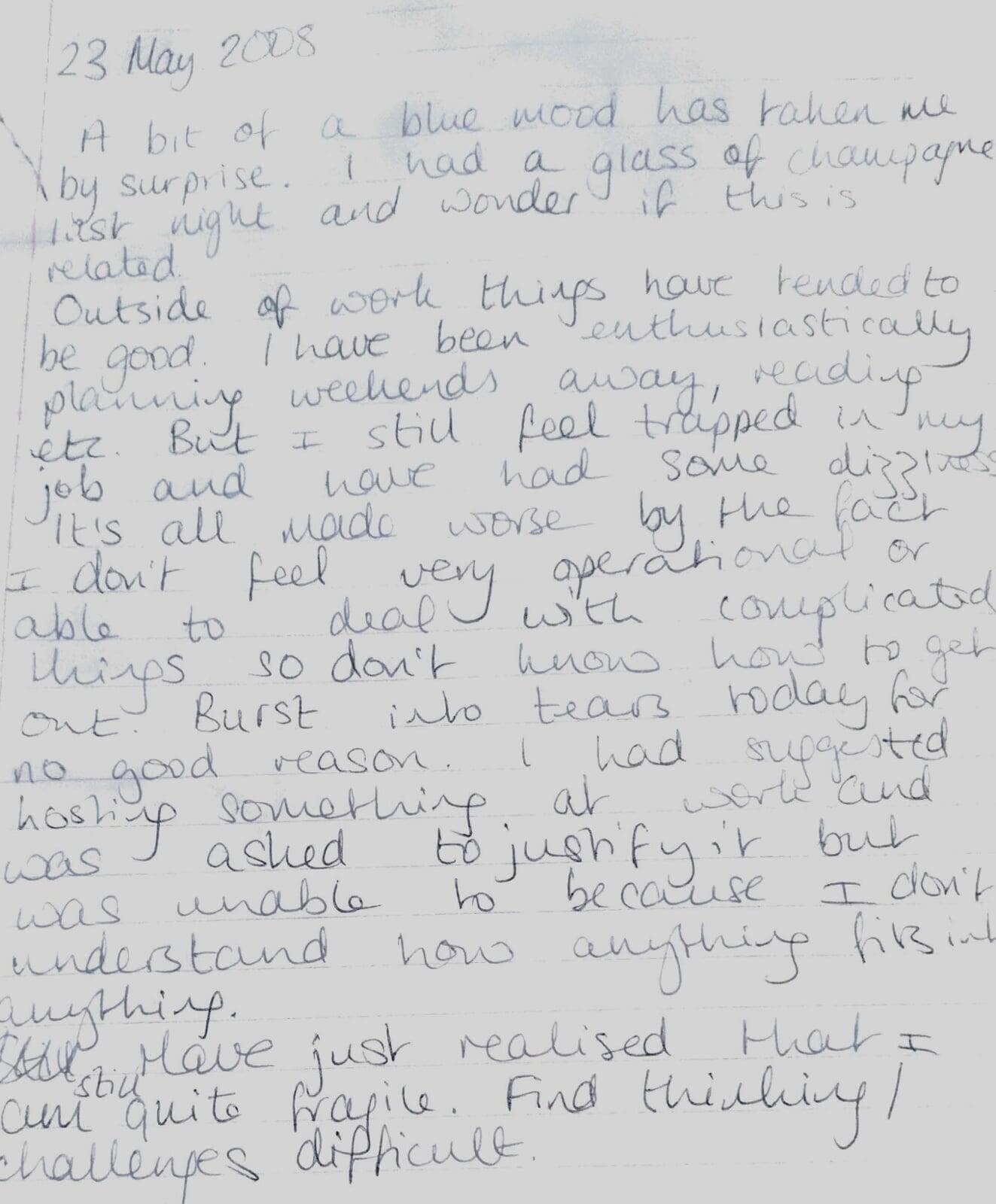

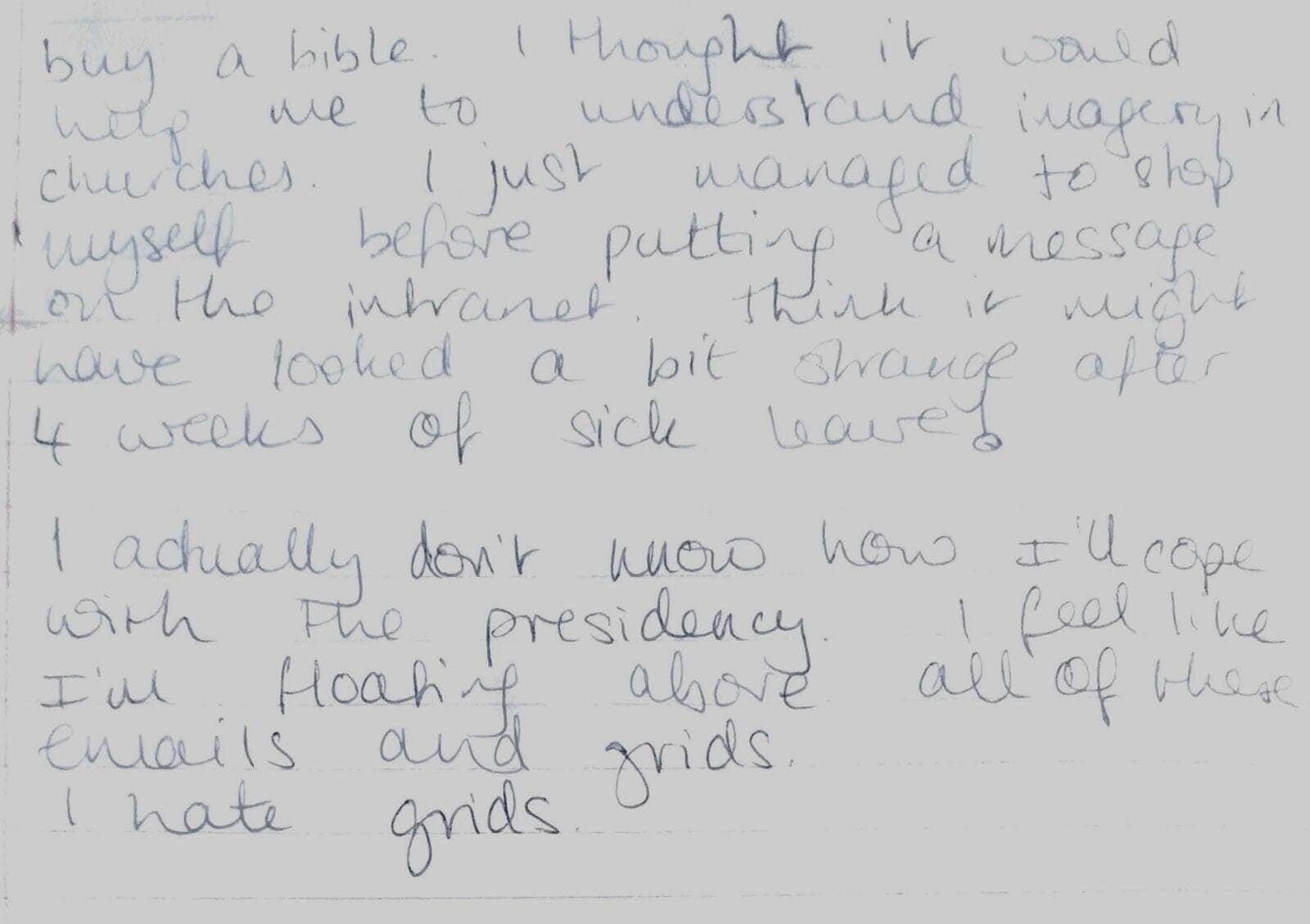

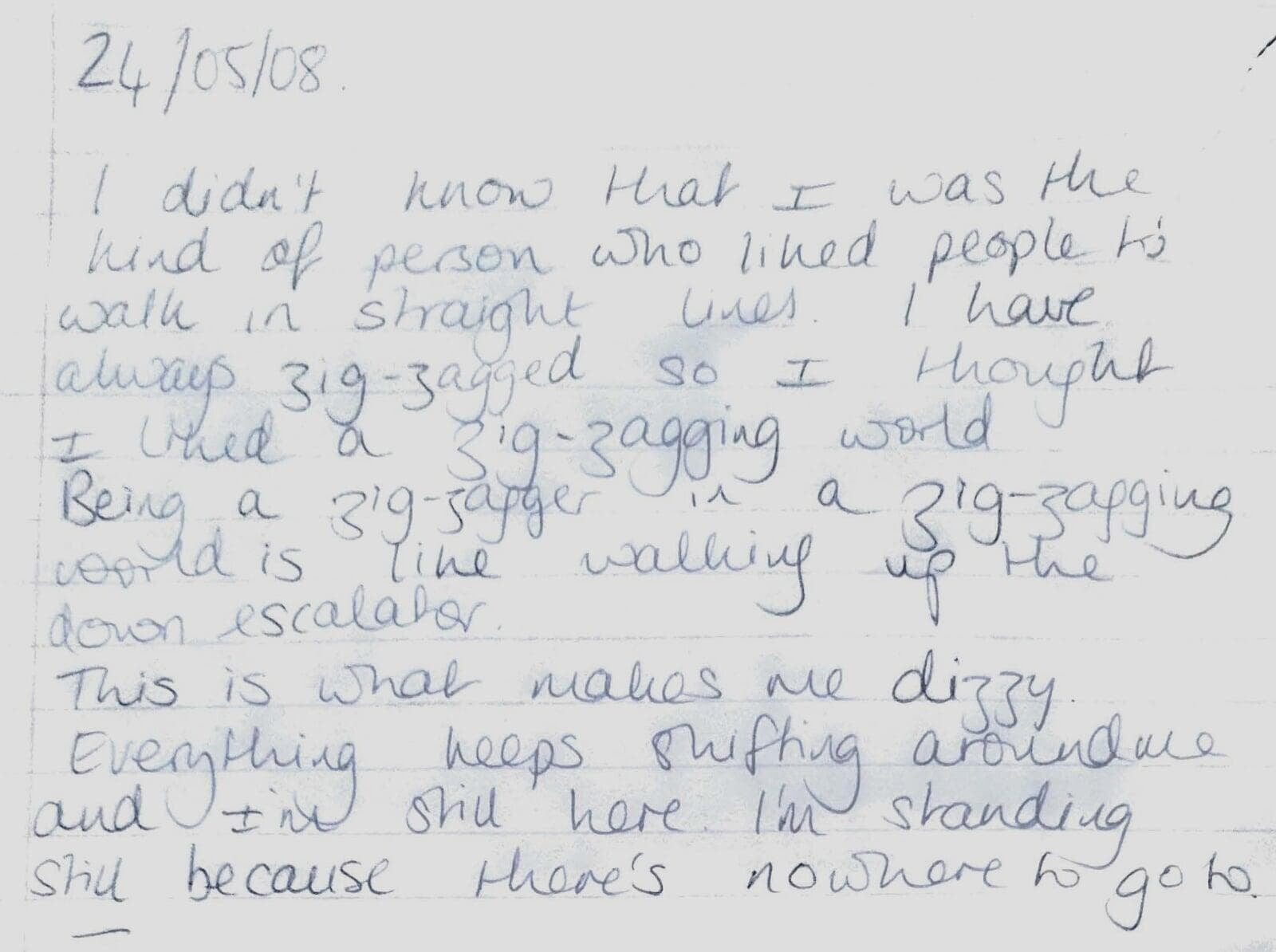

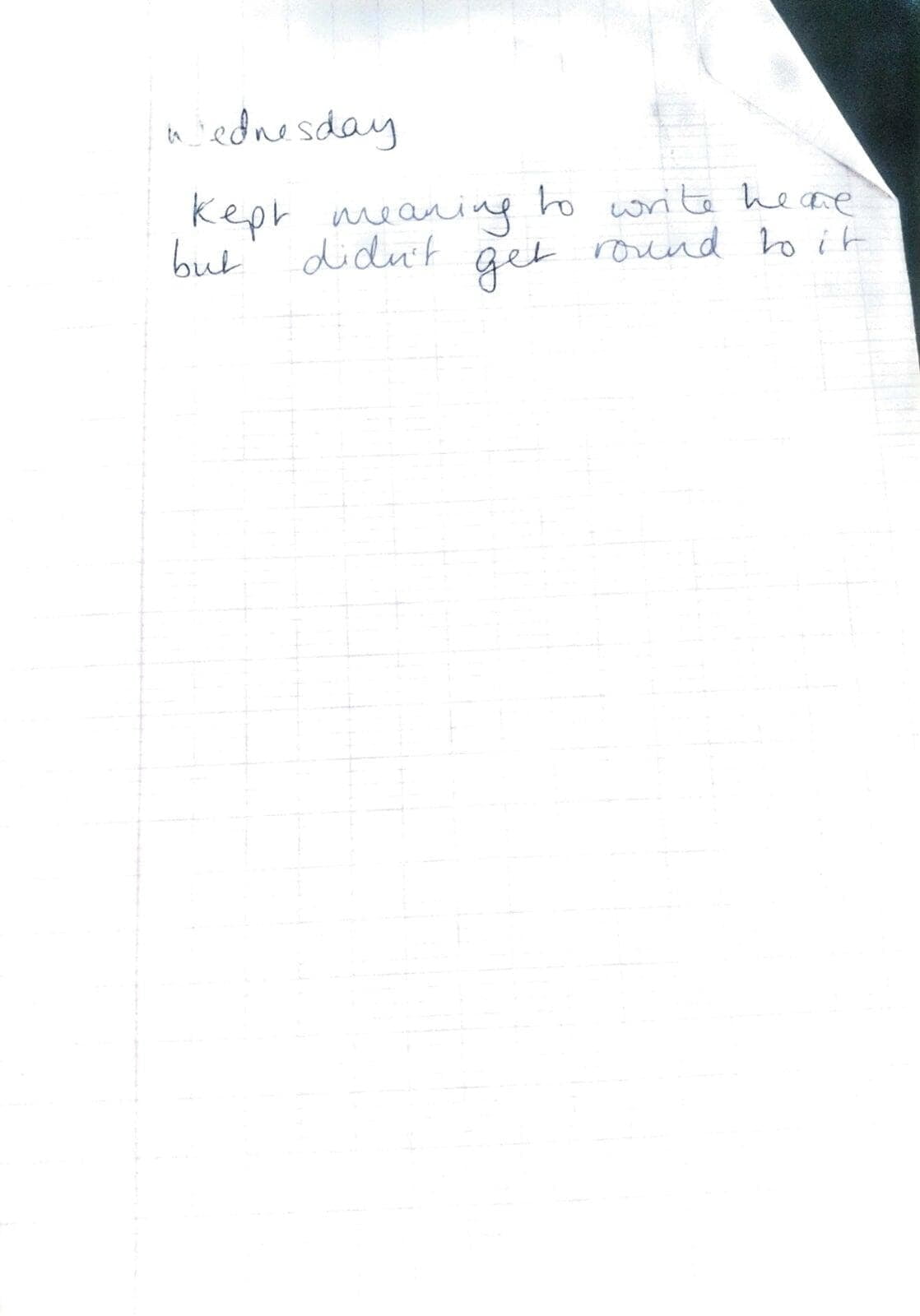

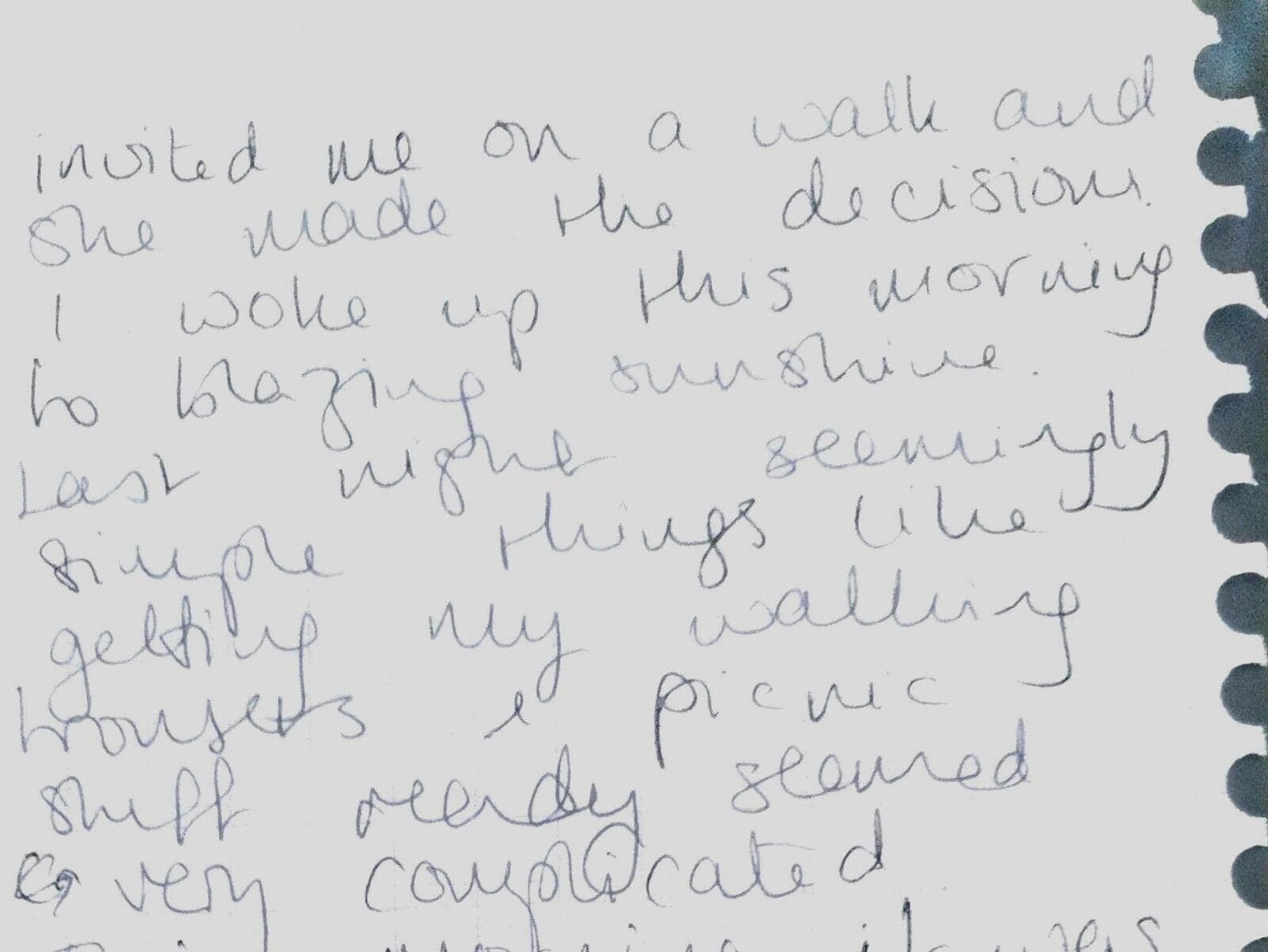

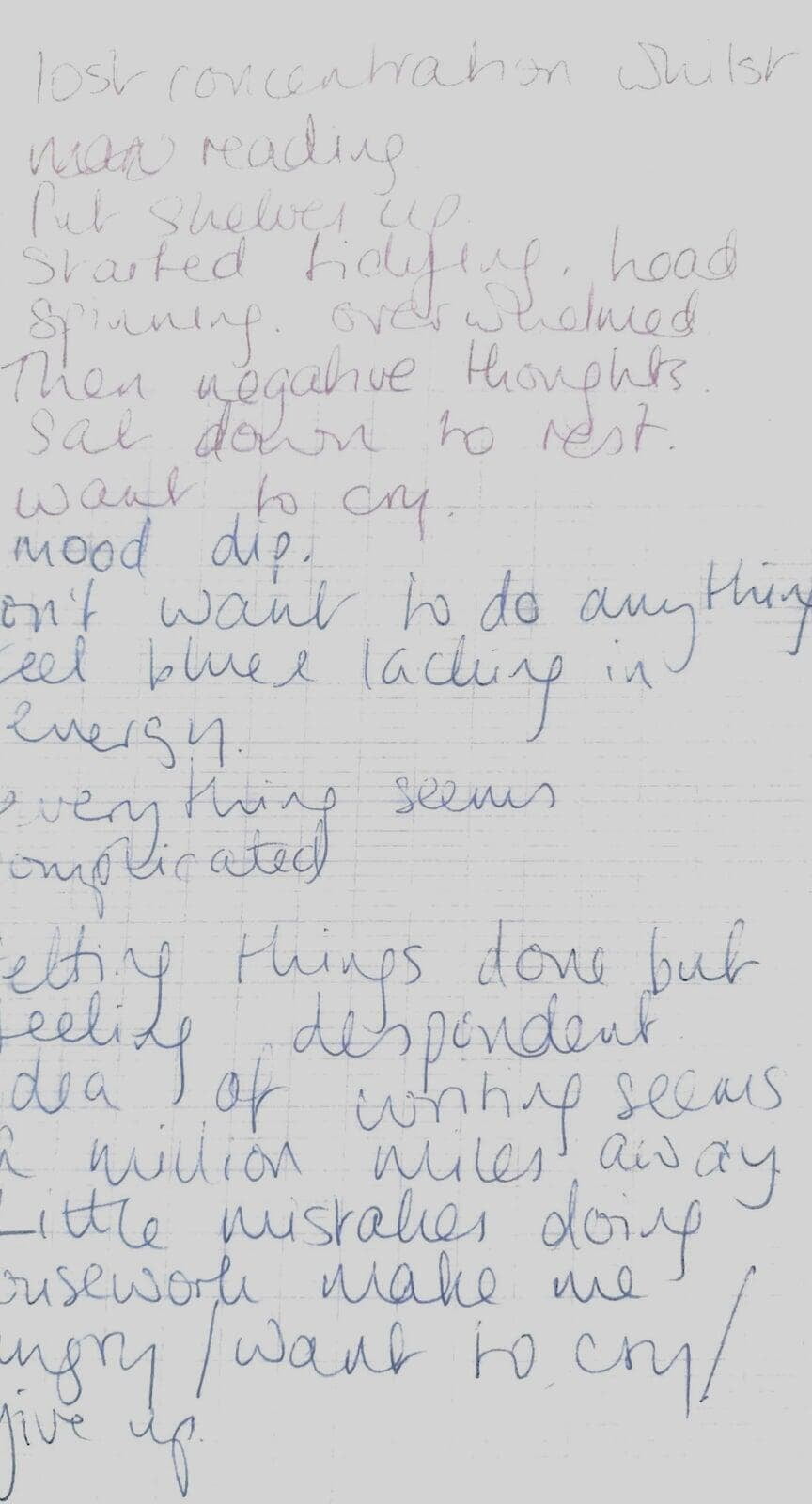

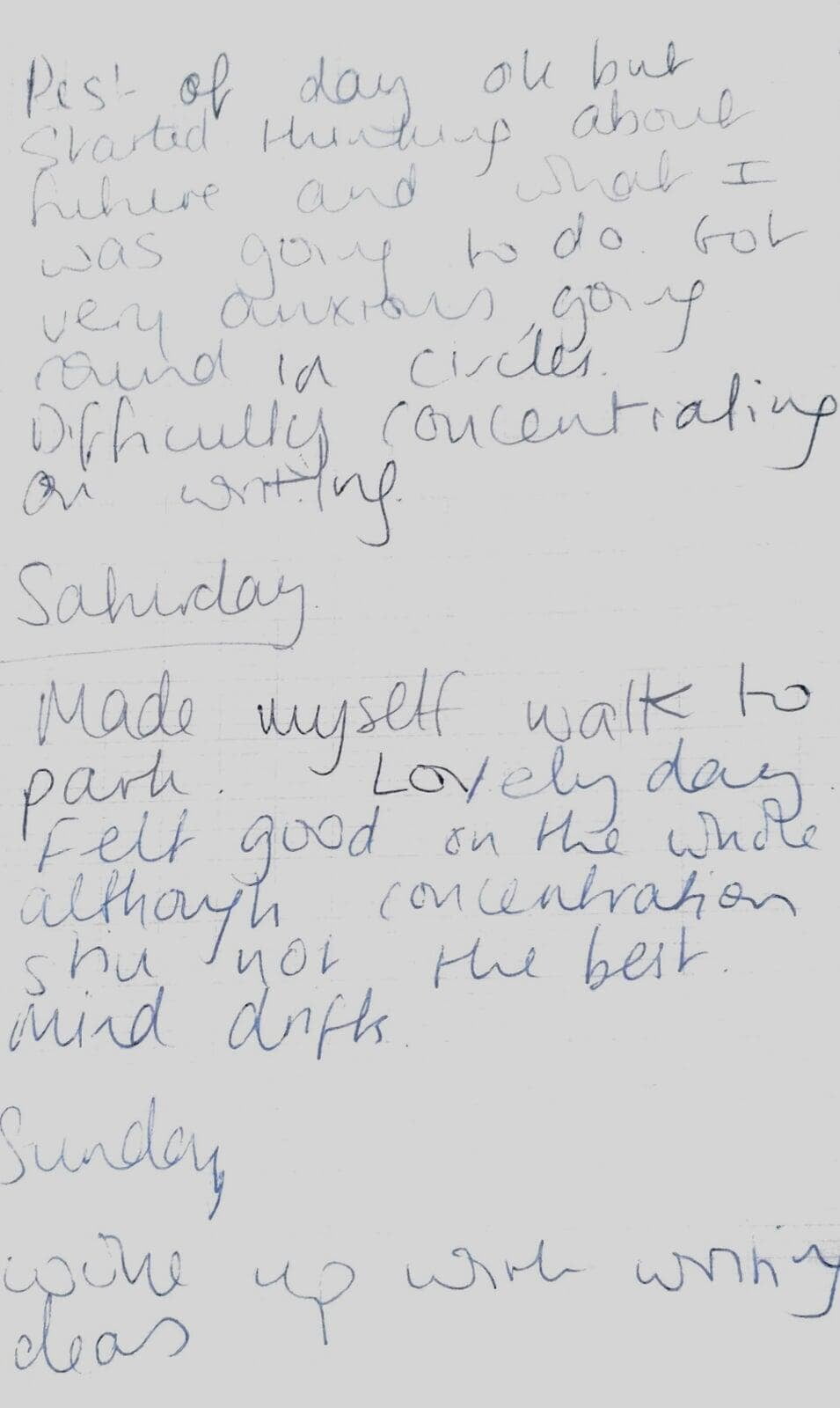

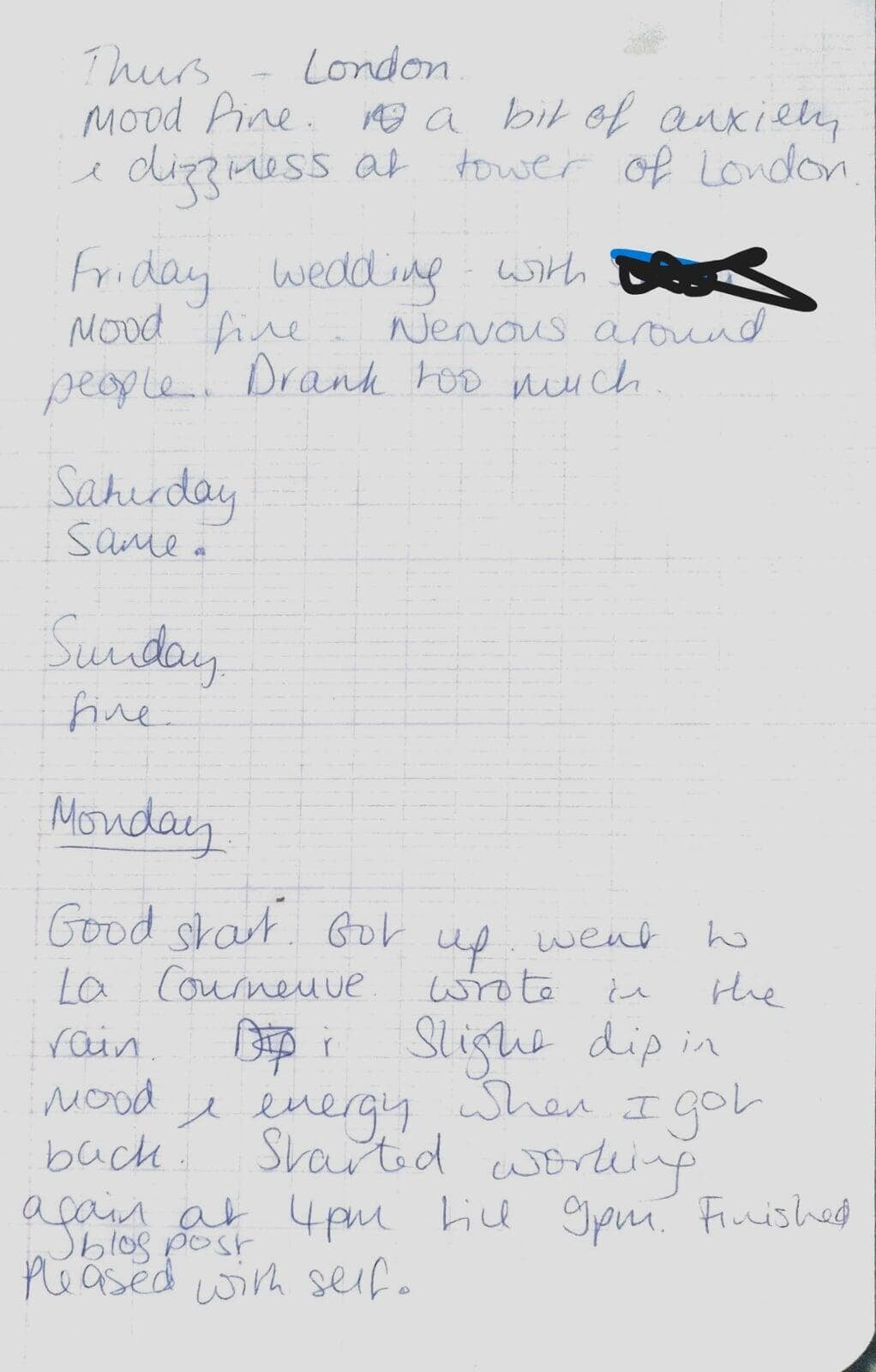

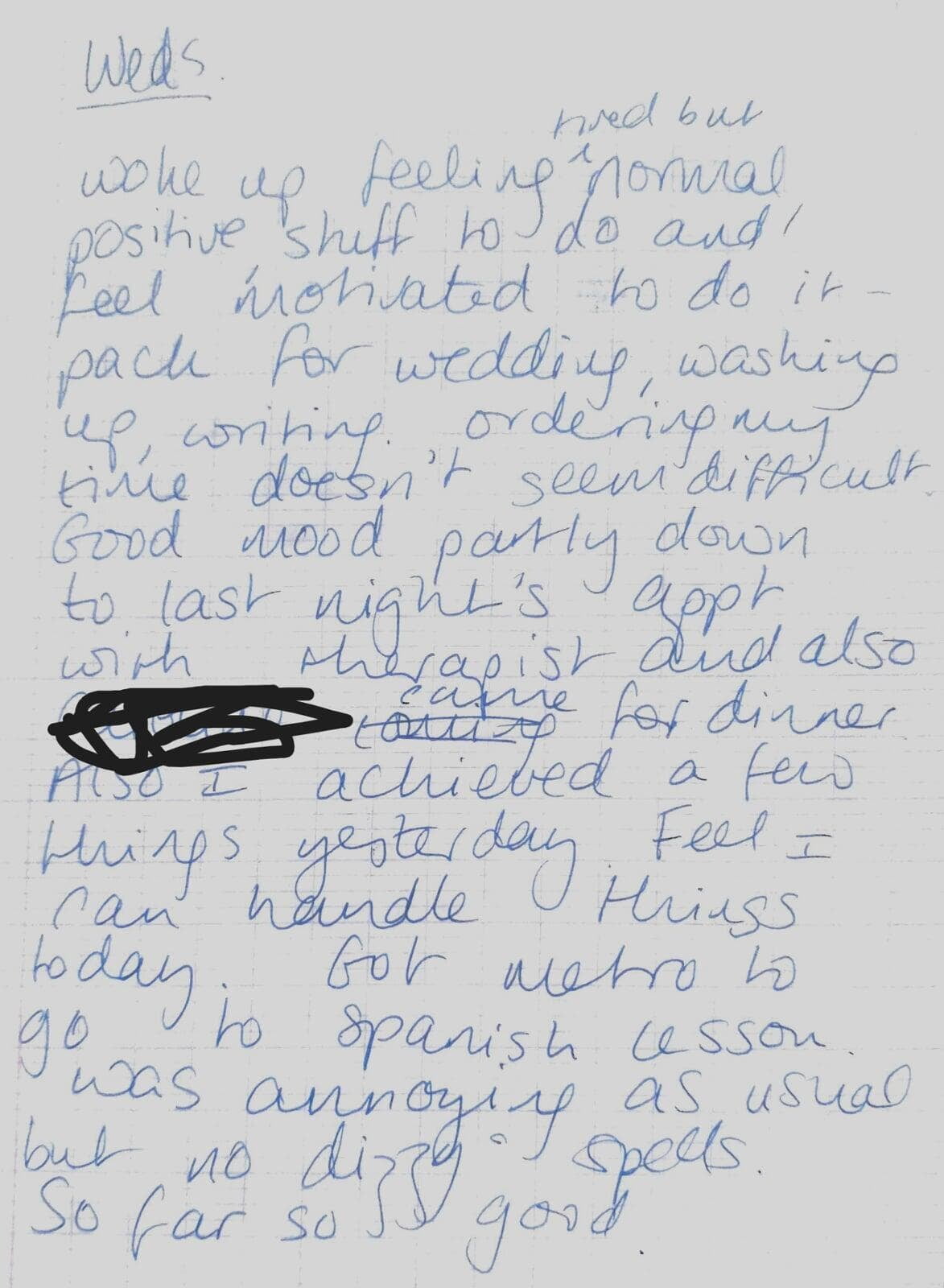

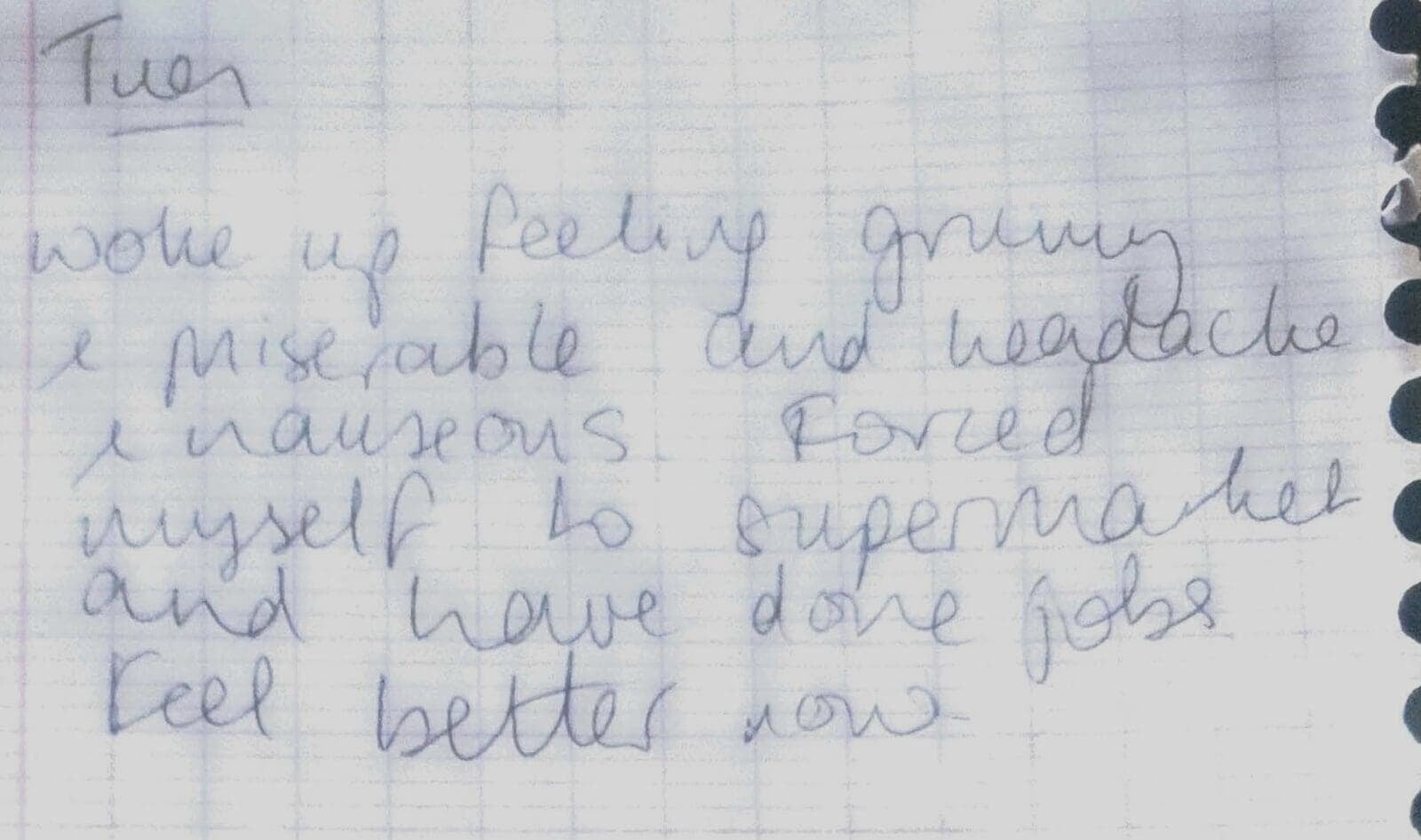

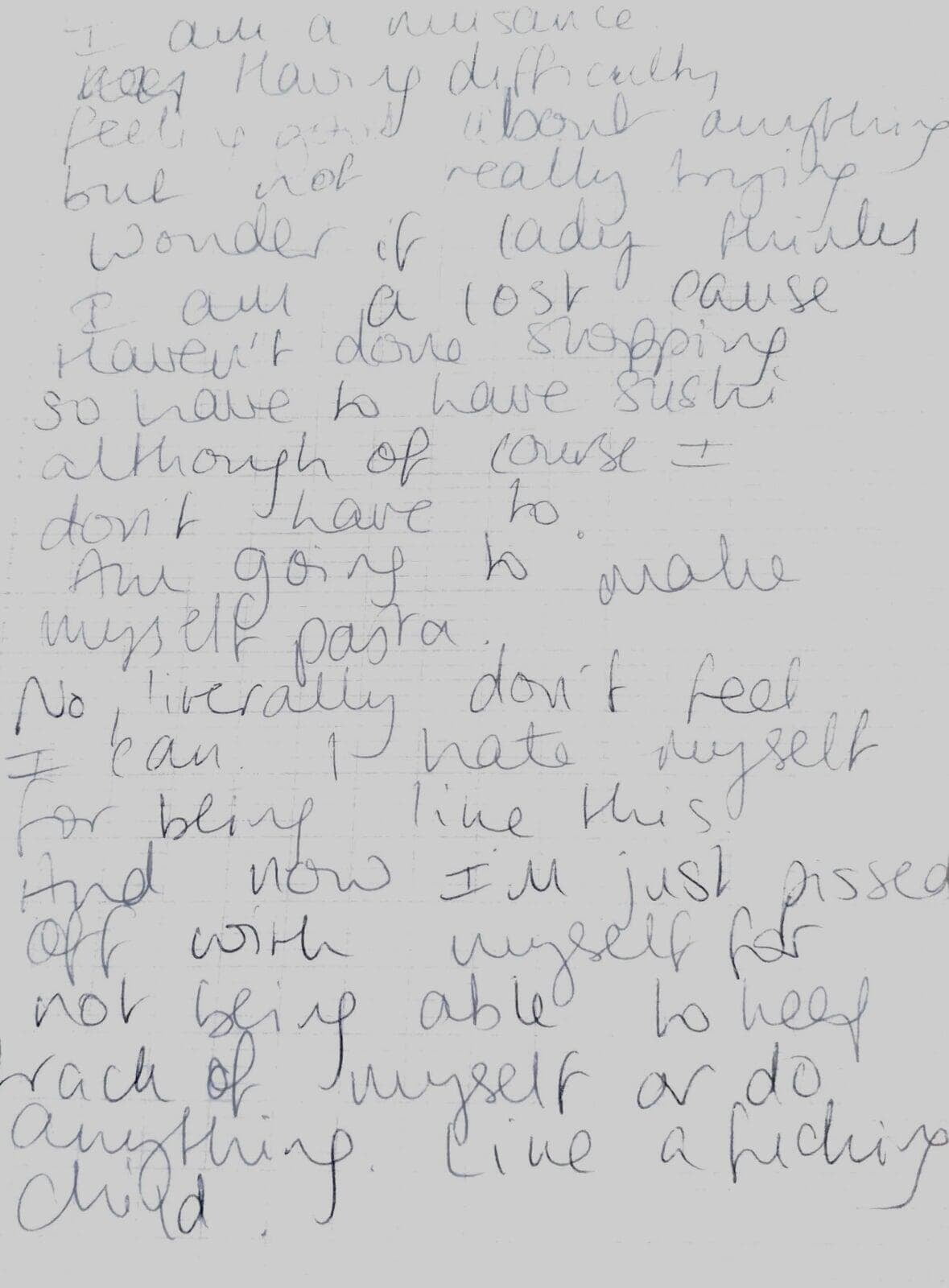

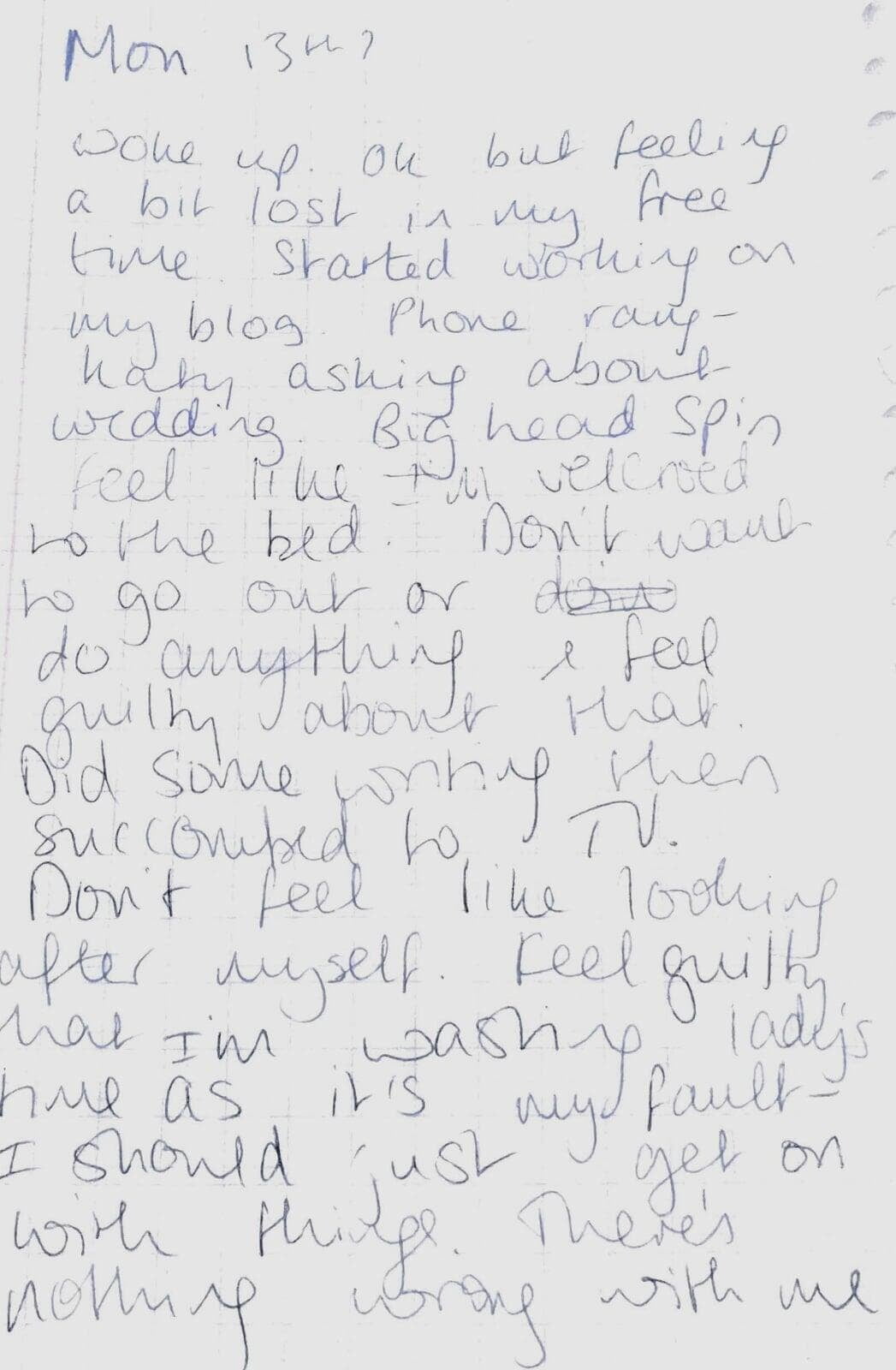

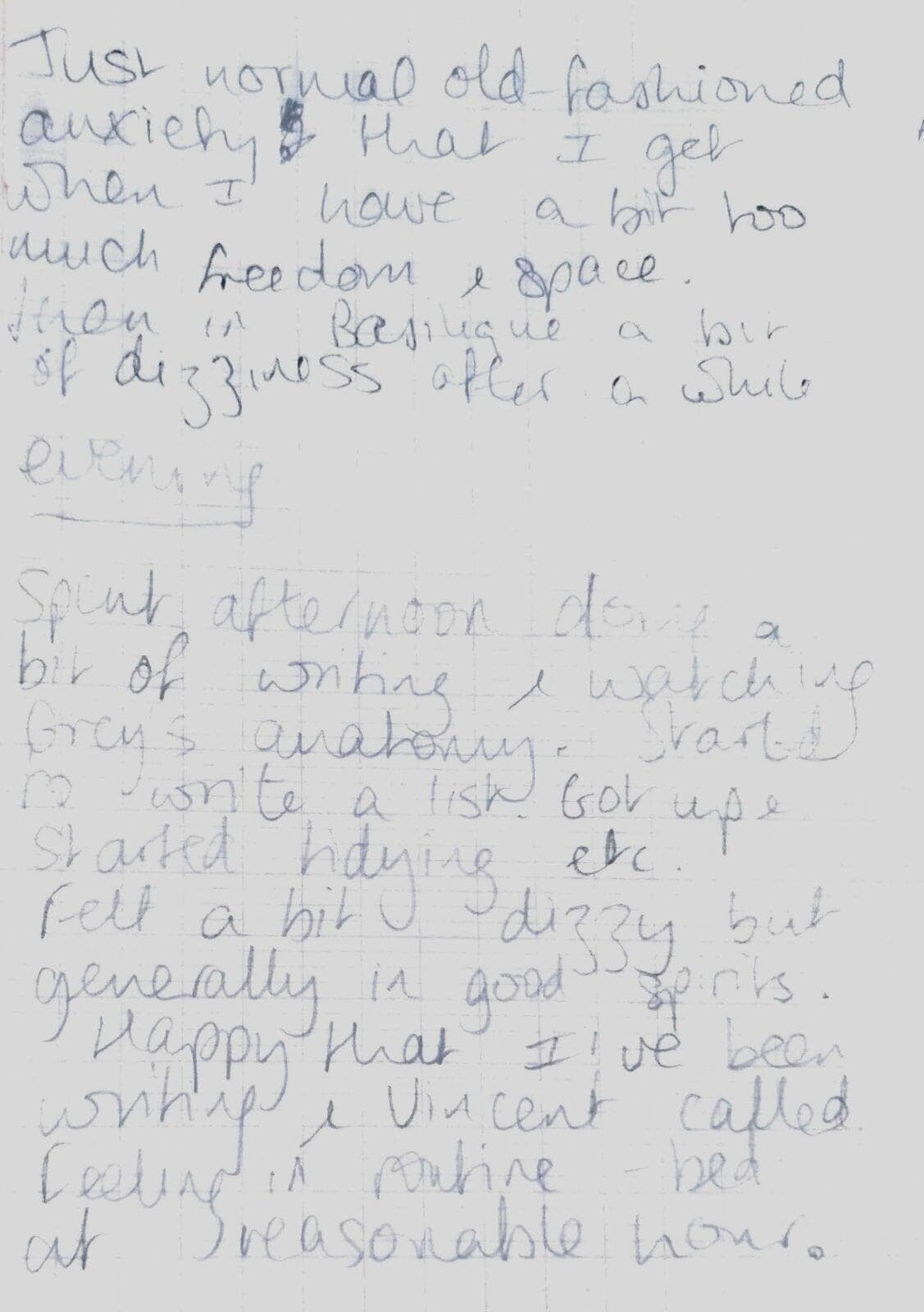

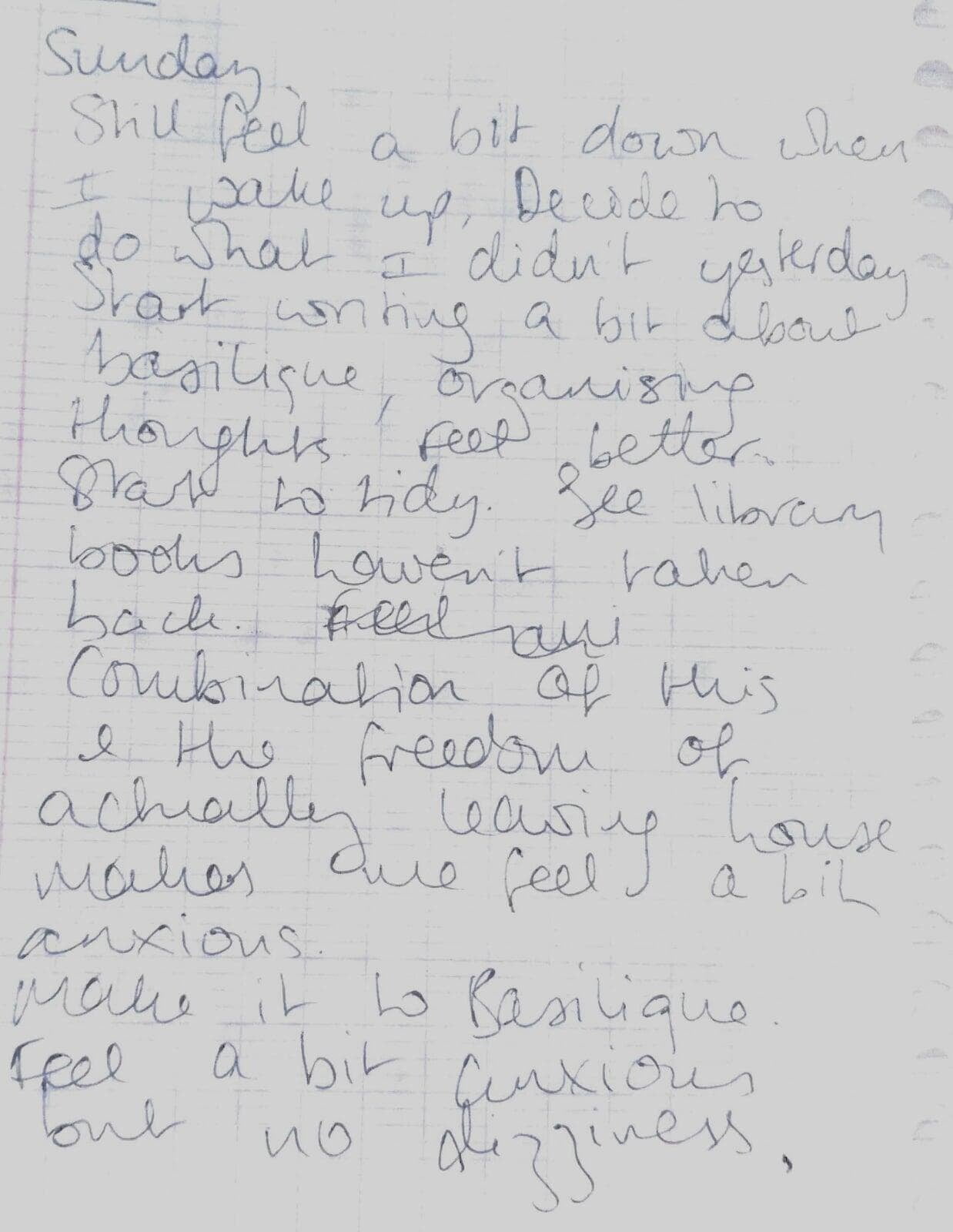

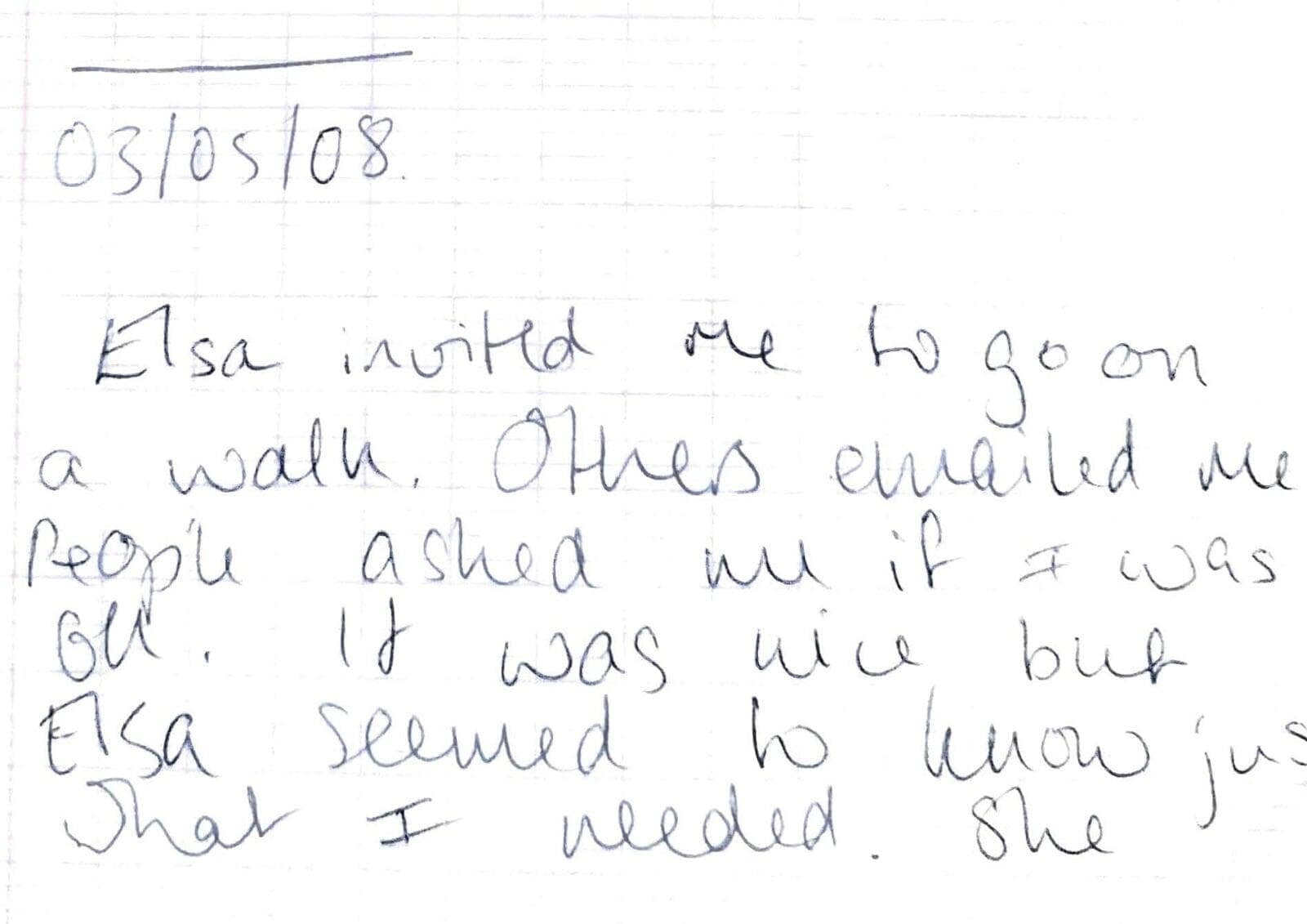

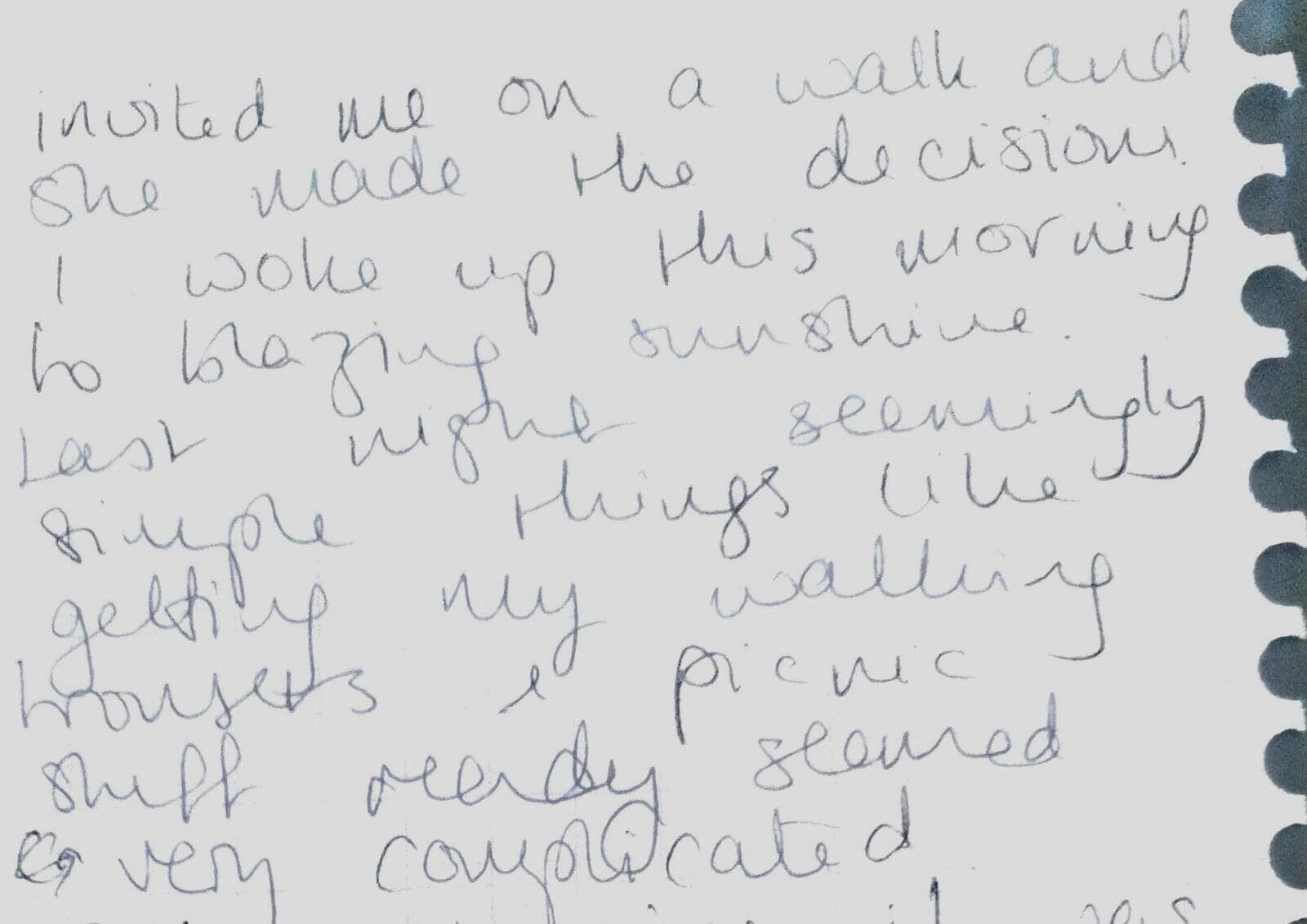

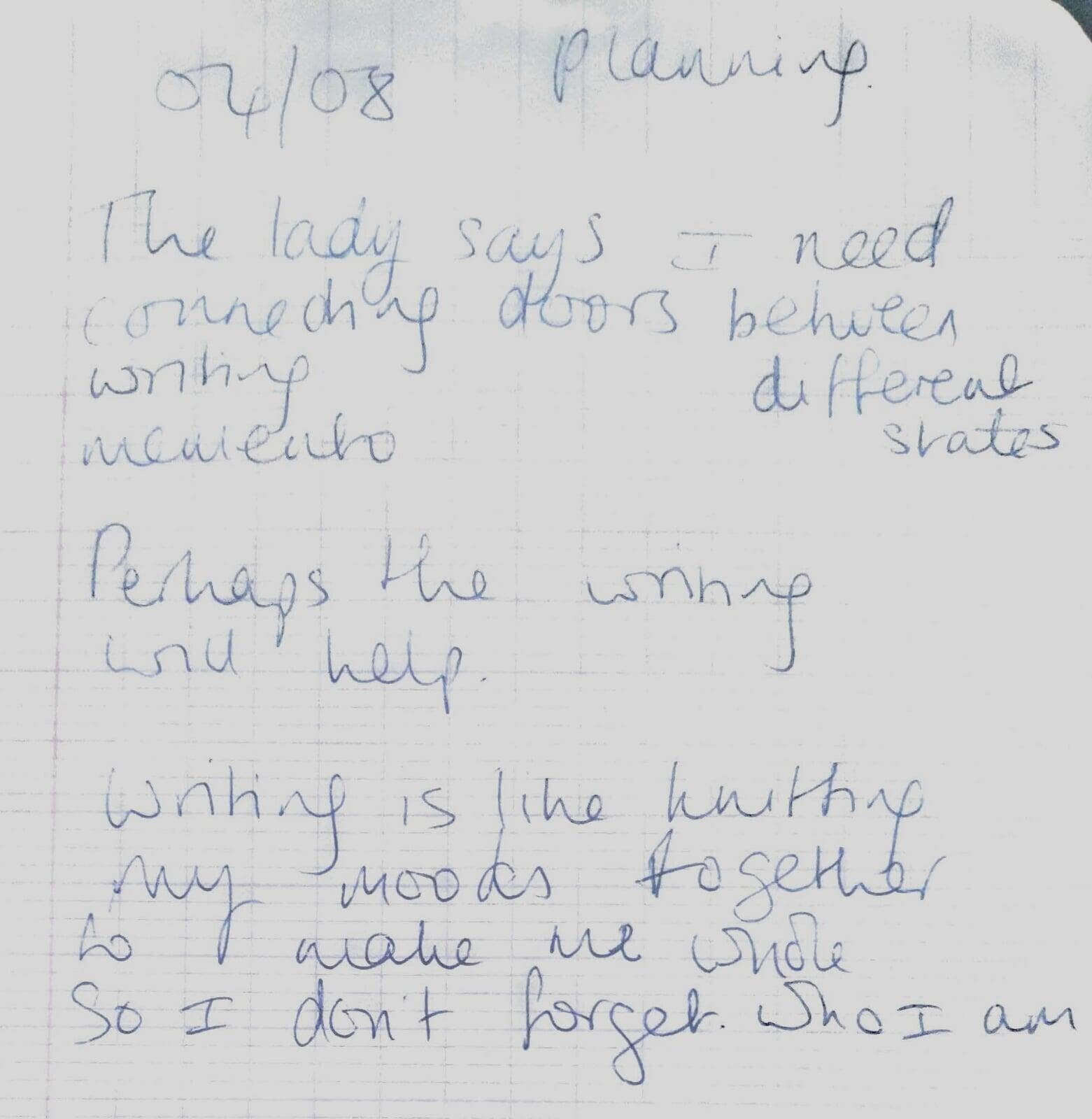

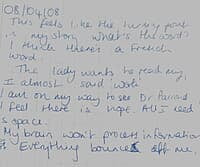

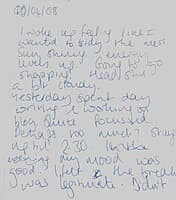

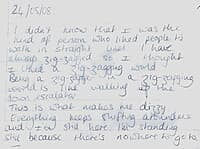

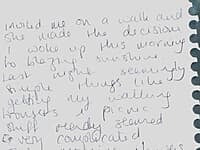

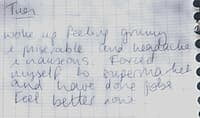

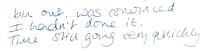

I spent a few weeks a home, feeling like an imposter for not being able to cope with work. This was the first and last time I managed to keep a symptoms diary. In it I put my “niggles” (hyperactivity) down to anxiety and my inattention down to my own shortcomings. I assumed that the indecisiveness, dizzy spells and forgetfulness were symptoms of my “depression” and the psychiatrist agreed. Little did I know that the Citalopram she prescribed me would be the sticking plaster that would thinly veil my traits right through until the menopause.

Over the years I have spent thousands and thousands of pounds and endless hours on different types of therapy. Every therapist was kind, compassionate and made me feel better in the short-term. And therapy taught me a lot about myself: that I’m really bad at remembering things, that I’m really bad at tracking things, that I’m incapable of improving or sticking to things, that I waste too much money, that I’m terrible at relationships, that I’m beyond help.

Some 15 years later and the understanding of adult ADHD has evolved but organisation, budgets and training in mental health services have not.

It was clear that I knew far more about my condition than every single professional I had been in contact with and that my words were meaningless to them. I was alone. An alien, the victim of a one-size-fits-all system in which those in crisis are placed on a conveyer belt towards a predetermined outcome: CBT. Far from offering me solutions, the system had made my mental health worse and eaten up valuable time and headspace that were already in short supply.

You can edit text on your website by double clicking on a text box on your website. Alternatively, when you select a text box a settings menu will appear. your website by double clicking on a text box on your website. Alternatively, when you select a text box

Therapies that are designed for depression and anxiety are not just ineffective for ADHD brains, they’re damaging. The confident claim that traditional CBT delivered by a non-specialist is an appropriate intervention for an ADHDer is not backed up by the evidence. Insisting that it is the silver bullet for someone with a neurodevelopmental condition who has been engaging with mainstream mental health services for decades and has been repeatedly misdiagnosed, is institutional gaslighting and yet one more tiresome example of neurotypical advice to “just try a bit harder”.

Asking someone who can barely remember to brush their teeth, whose period takes them by surprise every month and whose calendar stays open at January to set targets, to fill in diaries and complete worksheets on a regular basis is setting us up to fail.

Expecting someone who experiences time blindness, emotional dysregulation, poor working memory and poor self-assessment skills to fill in questionnaires and then using their meaningless responses to inform their future treatment and care is reckless. In short, most mental health services are detrimental to our mental health.

So what should you do instead?

If you have the money, contact a specialist neuroaffirmative provider like this one.

If you have some extra cash I suggest spending it on products or professionals who will help you compensate for your executive function challenges. Here are some examples:

Hire a cleaner

Hire a personal assistant.

Hire a personal assistant.

Buy extension towers and chargers like this one for each socket and at least one powerbank for when you leave the house.

Buy a subscription to Deepwrk, an excellent body double app that helps adults with ADHD improve focus, motivation and task completion

Buy software that helps you (I like Adobe Pro and Zoho).

If you can’t afford to pay for therapy or extra support, here are a few other options to improve your wellbeing:

Make an appointment with your GP’s social prescribing service. Whilst it is unlikely that they will be knowledgeable about ADHD, they do have more time to talk and find solutions to suit you. Another benefit is that they can act as a liaison with the GP, clarify any confusion and make sure your records are up to date.

Let all of your bank, energy providers, broadband providers and creditors know about your diagnosis and ask for reasonable adjustments (e.g. contact by email/post).

If you are in debt contact StepChange (if you are employed) or Business Debtline (if you are self-employed). You can also ask your GP to sign a mental health evidence form to send to your creditors. You may be able to reduce your debt or even have it written off completely.

If you are struggling with your mortgage payments you may be able to renegotiate your terms. Banks have signed up to the government’s mortgage charter banks and committed to helping those affected by the cost of living crisis.

If your files are a mess and you can’t find anything, start afresh. Submit a Right of Access Request to all of the companies and service providers you deal with regularly. You will receive a chronological file of all of your interactions with that provider. Make sure you ask for phone calls too. Ask for them to send it by email as a reasonable adjustment.

Download an app like Cube ACR and record your phone calls as a memory aide.

You may be entitled to benefits like PIP or Access to Work but not underestimate the energy and time involved and the scale of the task. Don’t apply for everything at once and reach out to a local charity for assistance. Insist on reasonable adjustments during the application process. If they say no, ask why and remind them of their obligations.

Most importantly of all, use the time you would spend in therapy hanging out with your tribe. Being with people who get you and having the freedom to be yourself is the best therapy of all.