Kimpa Vita and the Kongo Kingdom

Every now and then I have the opportunity to indulge in my first love: historical research. My research into the Kongo Kingdom for author Lilia Bongi was a real passion project. Click below to jump into the rabbit hole!

The city’s name comes from the Kikongo word for rocks: tadi, giving us a fleeting glimpse into the history of the Bakongo people.

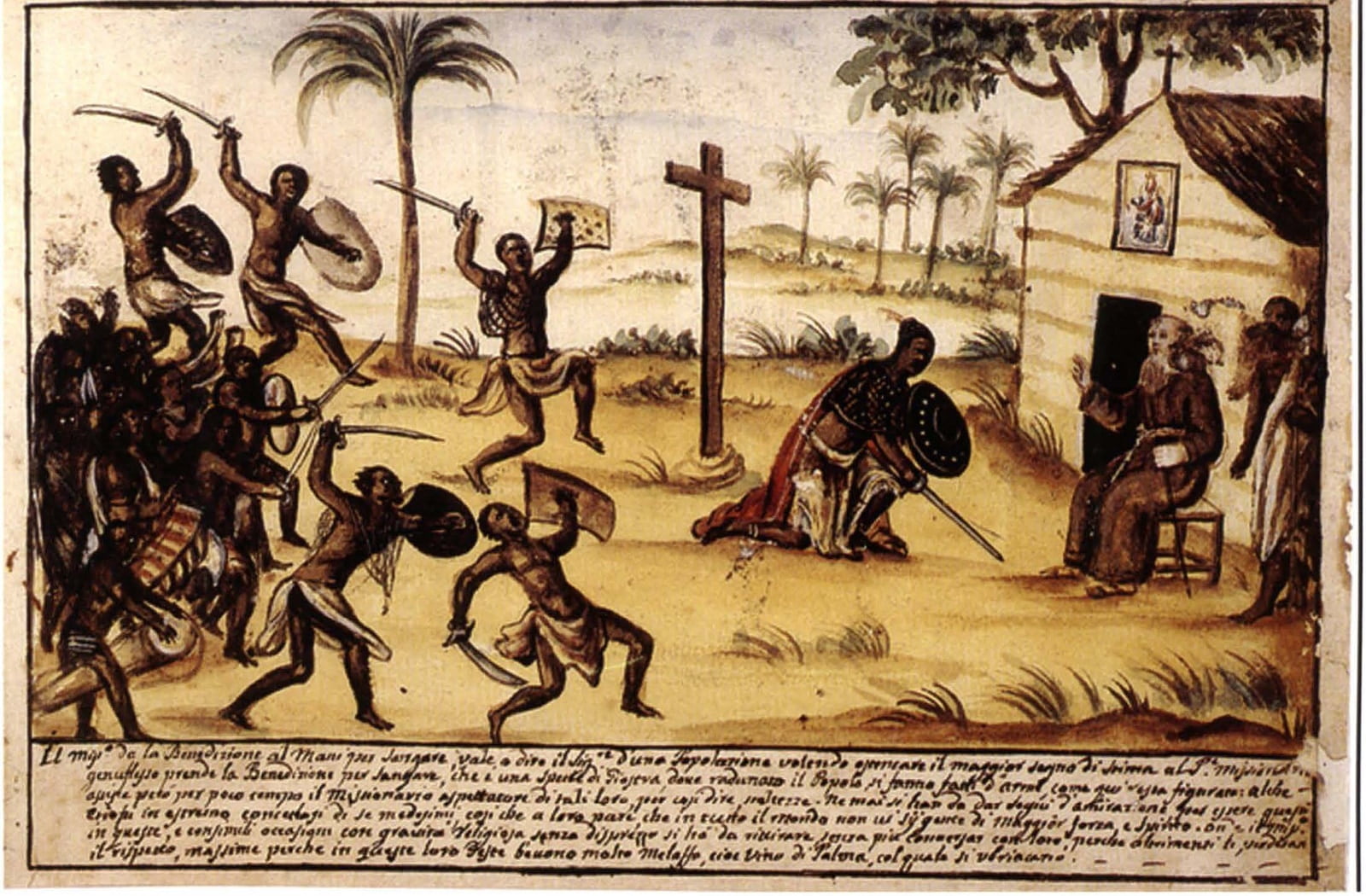

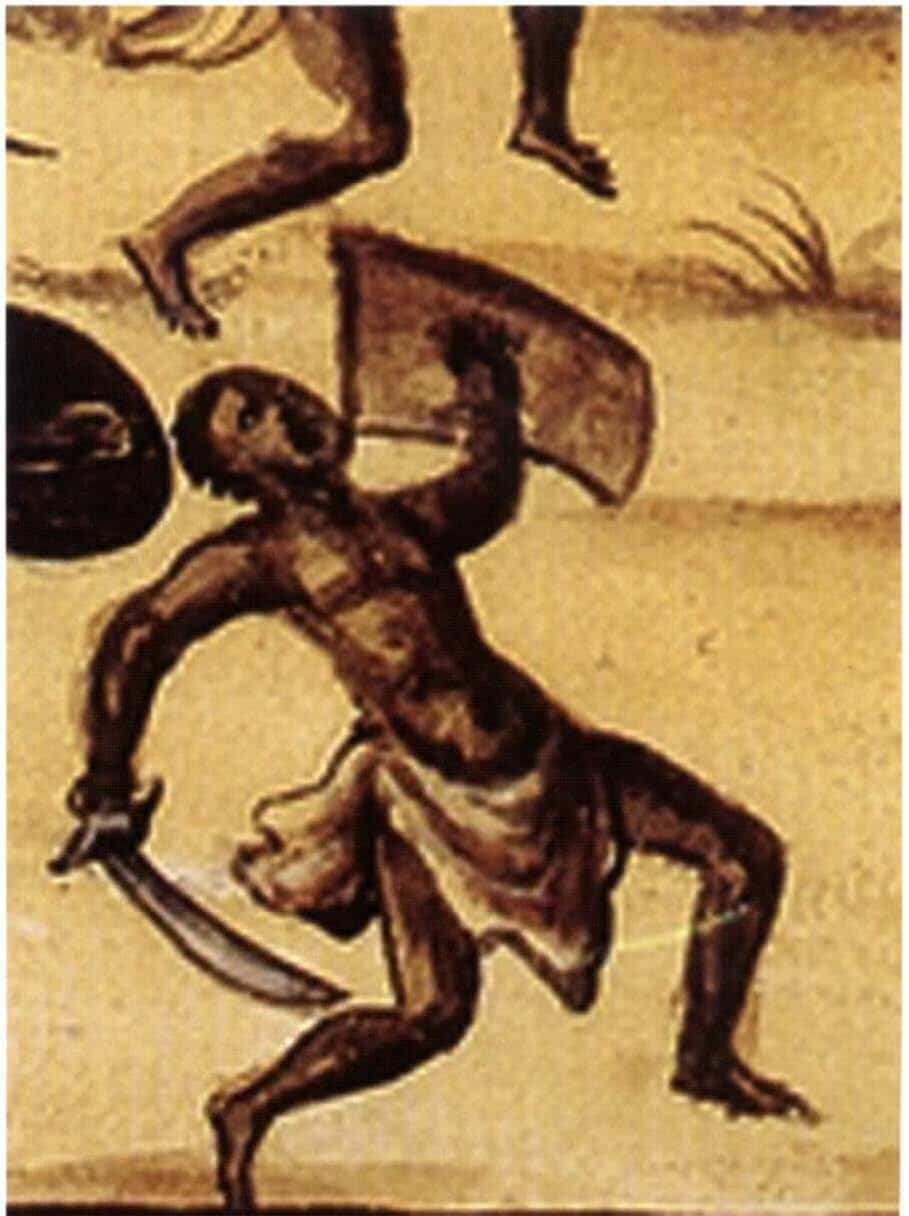

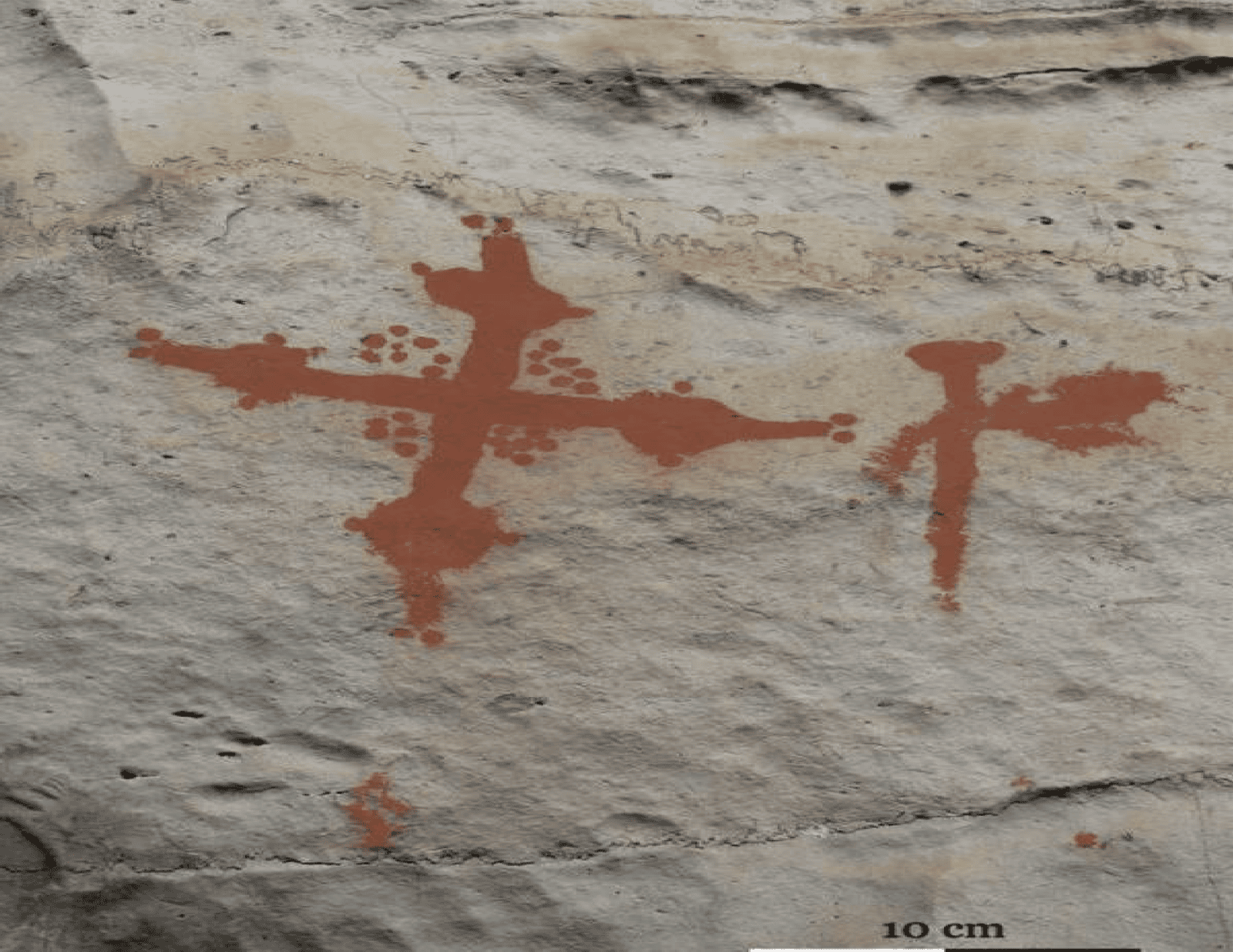

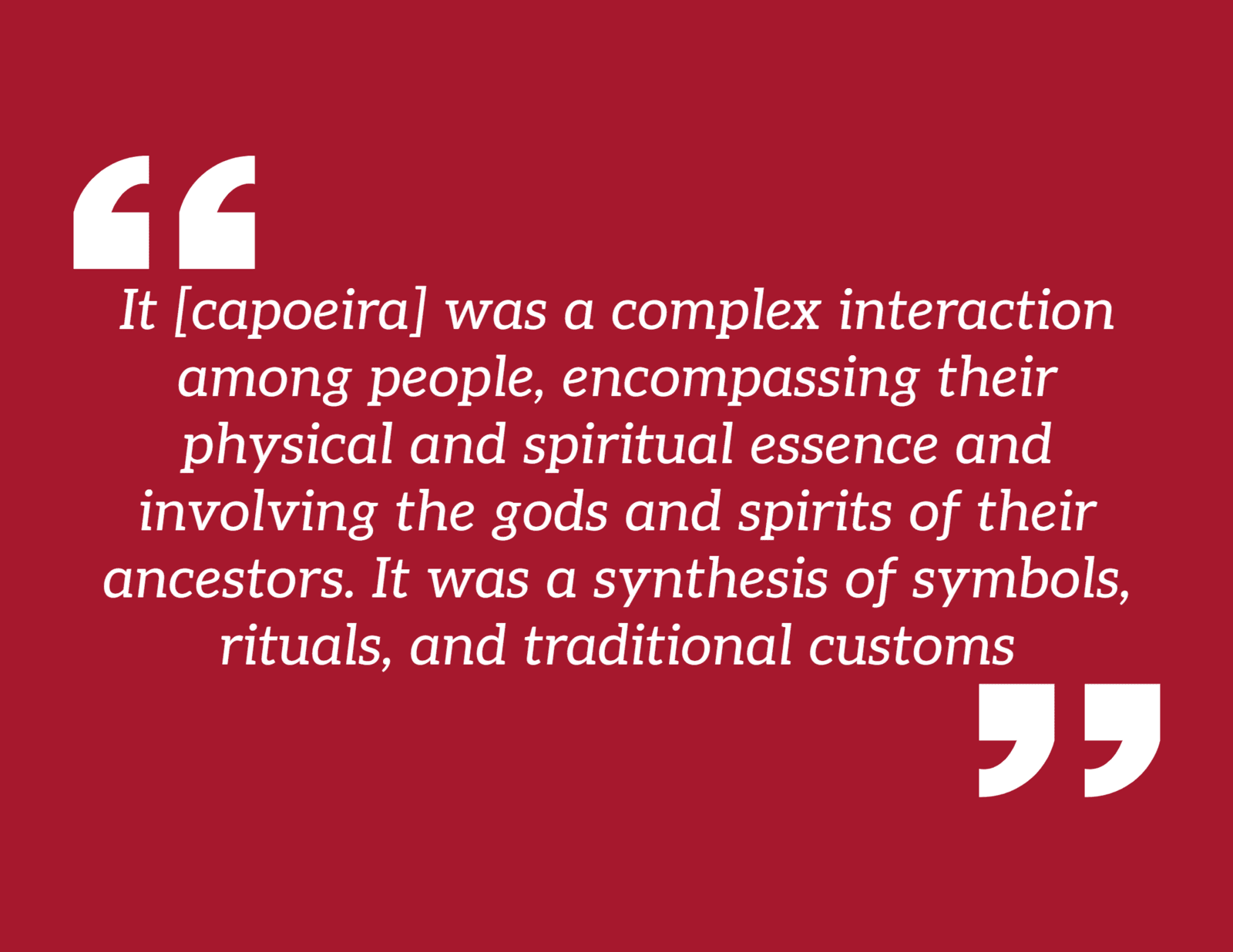

Pay close attention and you might spot other clues left behind by the ancestors: in the crosses painted on limestone outcrops around Lamba, the leopard head of the Congolese emblem, in capoeira dancing in Brazil

The Port of Matadi

The name comes from the Kikongo word for rocks: tadi, giving us a fleeting glimpse into the history of the Bakongo people.

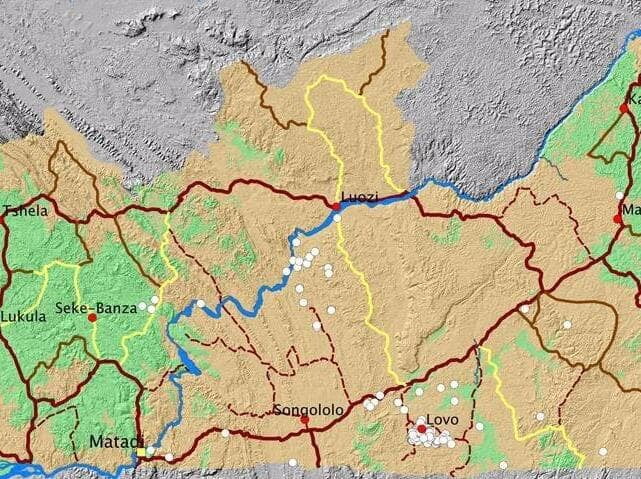

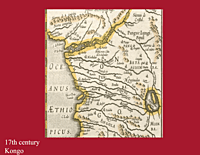

The Kongo River Basin

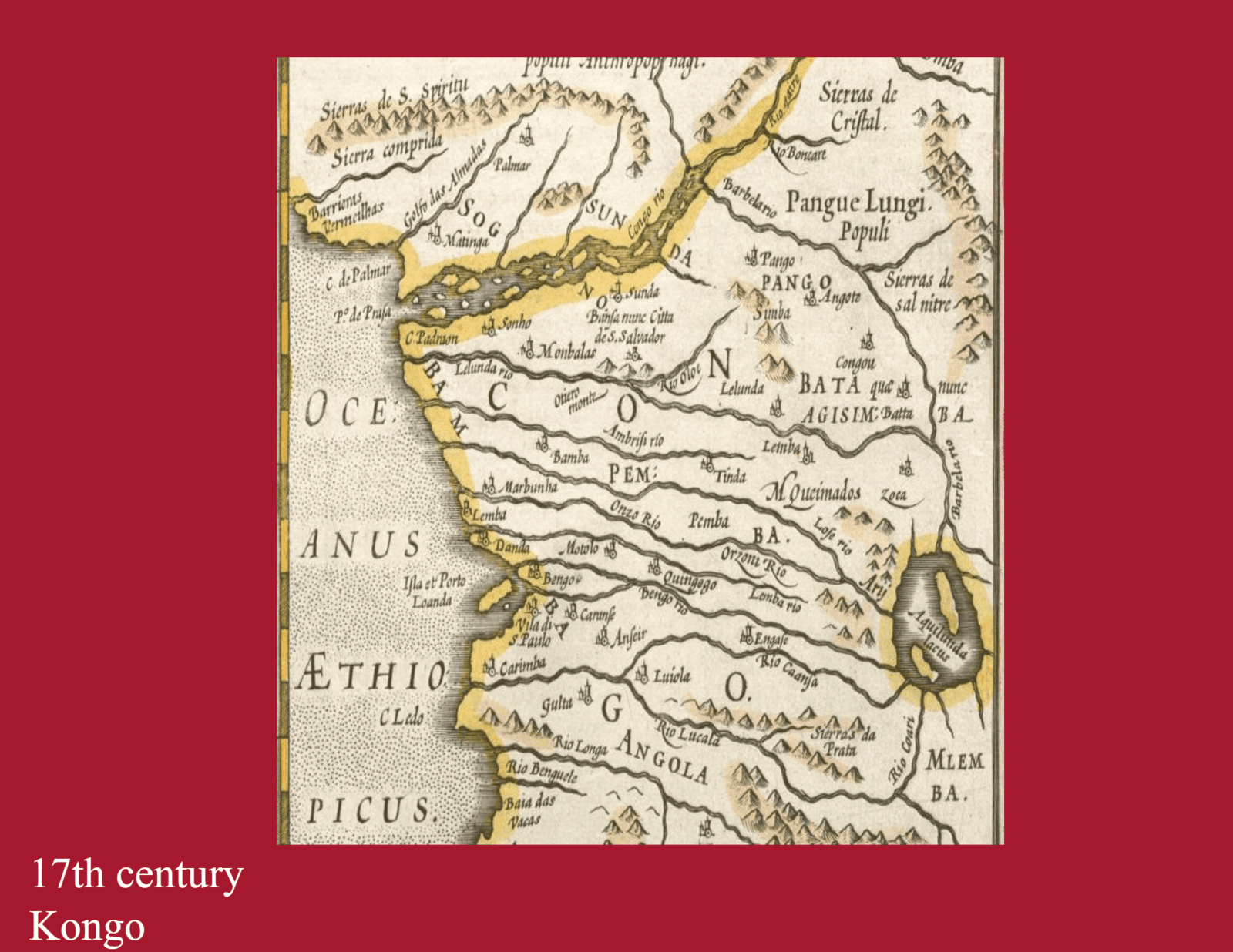

The second longest river in Africa, the name The name Congo/Kongo originates from the Kingdom of Kongo once located on the southern bank of the river.

The Lovo Massif is the largest concentration of rock art in the entire region

Heimlich, G., Richardin, P., Gandolfo, N., Laval, E., & Menu, M. (2013). First Direct Radiocarbon Dating of the Lower Congo Rock Art (Democratic Republic of the Congo). Radiocarbon, 55(3), 1383-1390. doi:10.1017/S0033822200048311

Map of Lower Congo showing the distribution ofrock-art sites

Heimlich, G., Richardin, P., Gandolfo, N., Laval, E., & Menu, M. (2013). First Direct Radiocarbon Dating of the Lower Congo Rock Art (Democratic Republic of the Congo). Radiocarbon, 55(3), 1383-1390. doi:10.1017/S0033822200048311

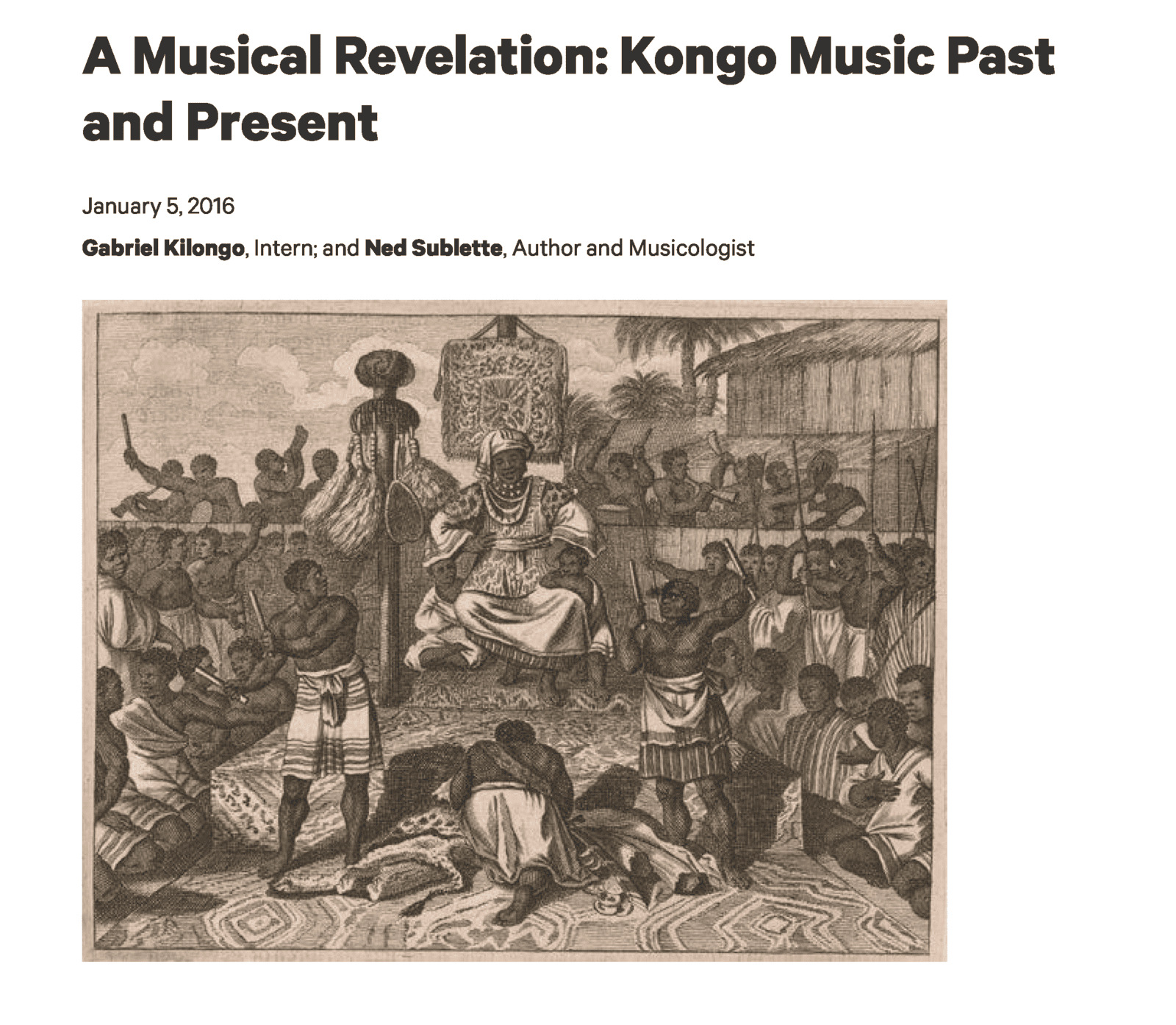

Kongo Music Past and Present

Ned Sublette, Author and Musicologist A Musical Revelation: Kongo Music Past and Present

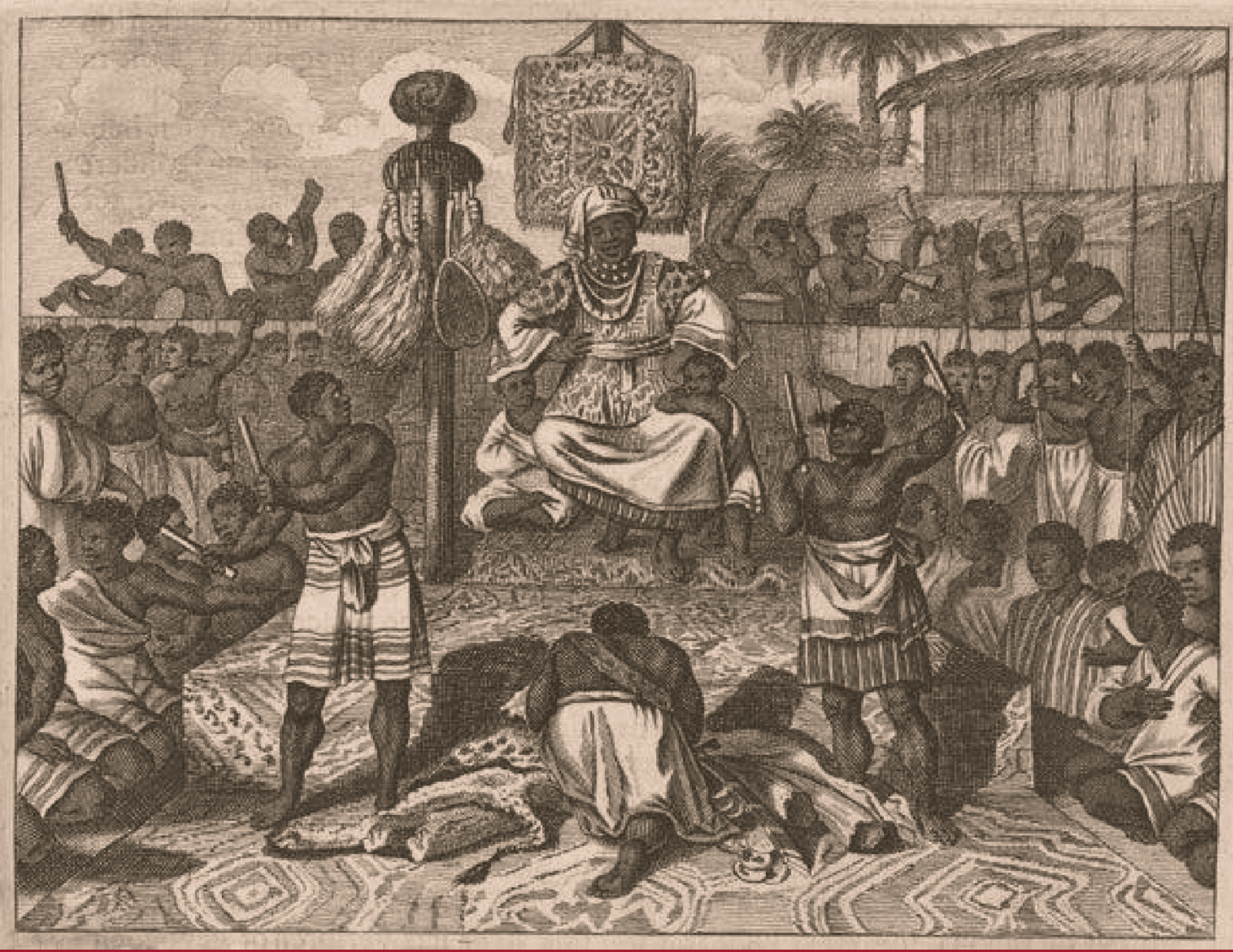

Trumpeters appear in a seventeenth-century depiction of the court of the neighbouring King of Loango

ing of Loango (Maloango) engraving from O[lfert] Dapper, Naukeurige Beschrijvinge (Amsterdam), p. 539, 1686. H. 14 9/16 x W. 9 13/16 x D. 2 9/16 in. (37 x 25 x 6.5 cm). Library Gigi Pezzoli, Milan

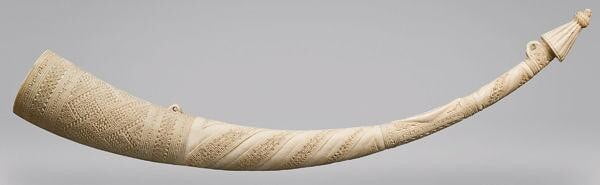

16th century olipahnt

Kongo peoples, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kongo Kingdom; Republic of the Congo; Angola. Ivory; H. 32 5/8 in. (83 cm), Diam. 3 in. (7.5 cm). Palazzo Pitti, Museo degli Argenti, Florence (Bg. 1879 avori, n.2).

The hidden history of Capoeira

Talmon-Chvaicer, M.. (2008). The hidden history of Capoeira: A collision of cultures in the Brazilian battle dance. 1 -237.

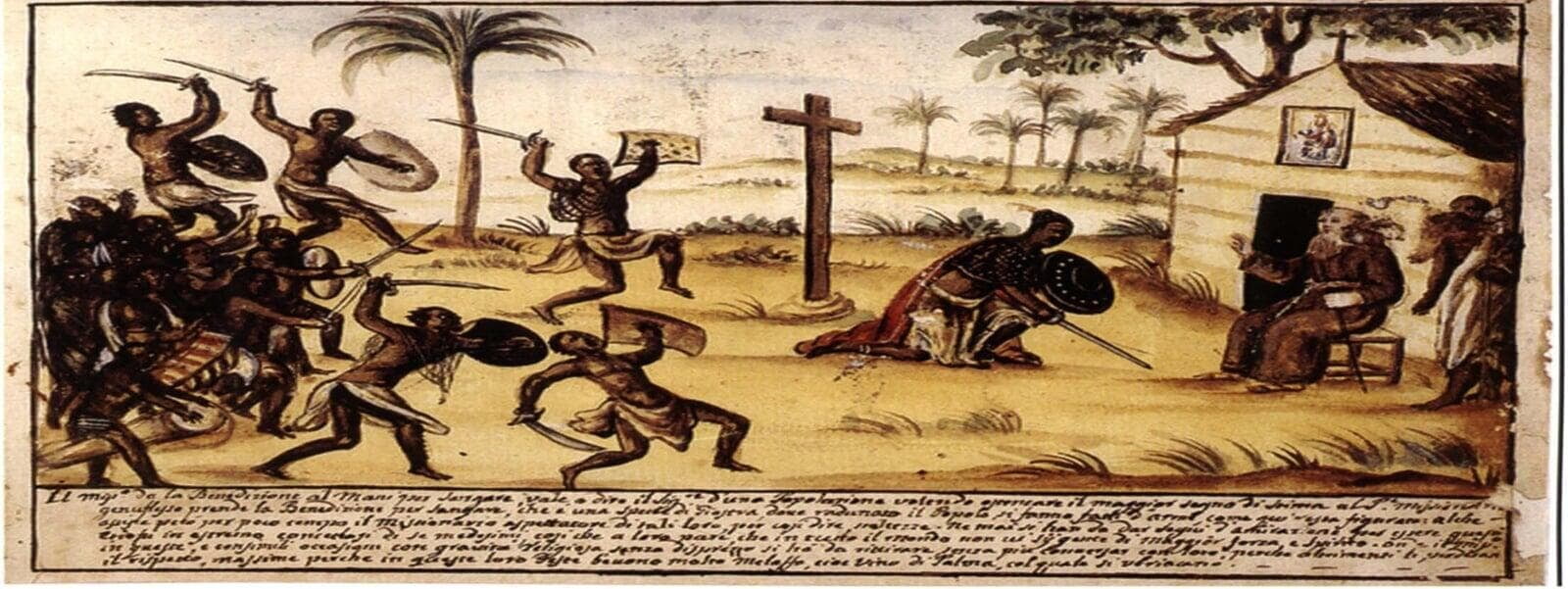

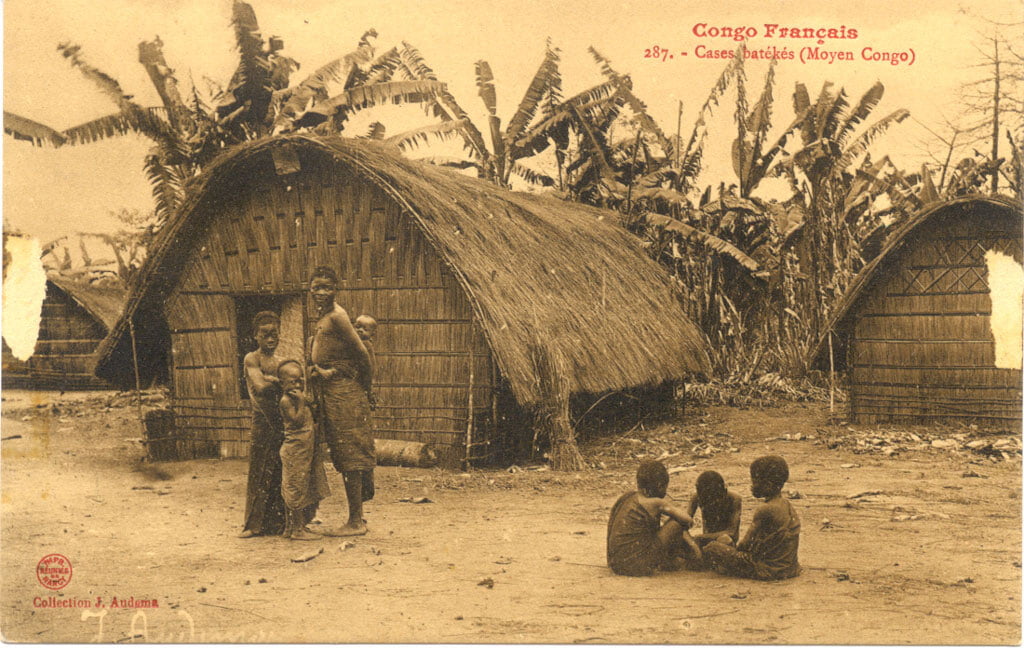

The Missionary Gives his Blessing to the Mani during Sangamento

Bernardino d'Asti (Italy, ea. 1740) Watercolor on paper; 19.5cm x 2 8cm (7¾" x 11") Biblioteca Civica Centrale,Turin, MS 457, fol. 18

Title

Caption

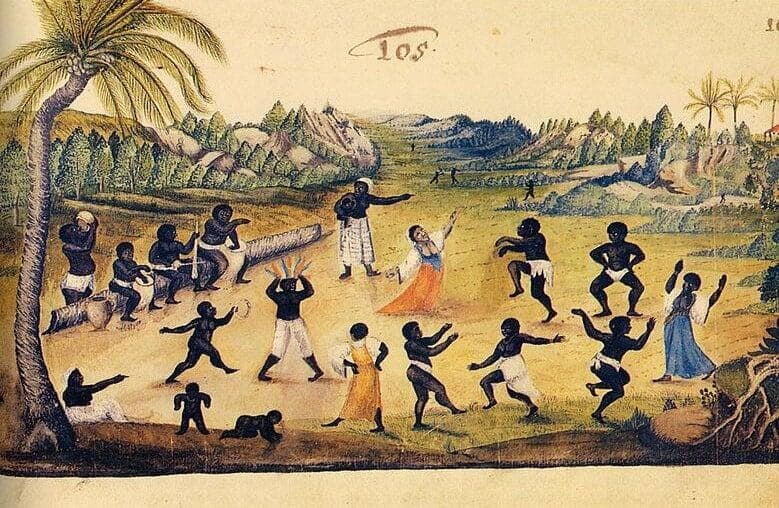

Divination ceremony and dance in Brazil

Talmon-Chvaicer, M.. (2008). The hidden history of Capoeira: A collision of cultures in the Brazilian battle dance. 1 -237.

Emblem of the Democratic Republic of the Congo

The current emblem of the DRC depicts a leopard head, surrounded by an elephant tusk to the left and a spear to the right.

The chief was a man of great status and a slit drum would have been played whenever he was addressed.His raffia cap and headdress signified his rank but the leopard teeth that adorned his headwear and the leopard skin around his neck was more than a mere status symbol. Through them the chief was imbued with the leopard’s strength and power.

At village councils, called palavers, a drum called a mondo would have been played as the chief administered justice. Punishment included fines, beating, scalding, enslavement death and ostracism, depending on the severity of the crime.

The chief was assisted by the n’ganga who would put the wrongdoer through various ordeals and use his powers of divination to establish guilt or innocence.

The n’ganga was a herbalist and spiritual healer who also had a high status. He wore leopard-skin clothing decorated with bird feathers and used clay from the river bed to paint white circles around his eyes to help him detect evil forces. His frightening appearance would have inspired awe among the villagers.

Ordinary people could do magic, or kindoki, and might be contacted by ancestors through omens or dreams. However, with the exception of a gifted few, like twins and albinos, only banganga could communicate with them directly.

The nganga would have kept magical substances called bilongo in his nkisi, a hollowed- out figure that embodied the spirit of one of his ancestors. Its contents, would have been imbued with spiritual force and might have included herbs, claws, leaves or feathers.

However the key ingredient would have been clay and this would provide extra protection since it was extracted from the riverbed, where the ancestors resided.

Most baganga were men but some were women. Later we will meet a young woman nganga in another part of the Kingdom.

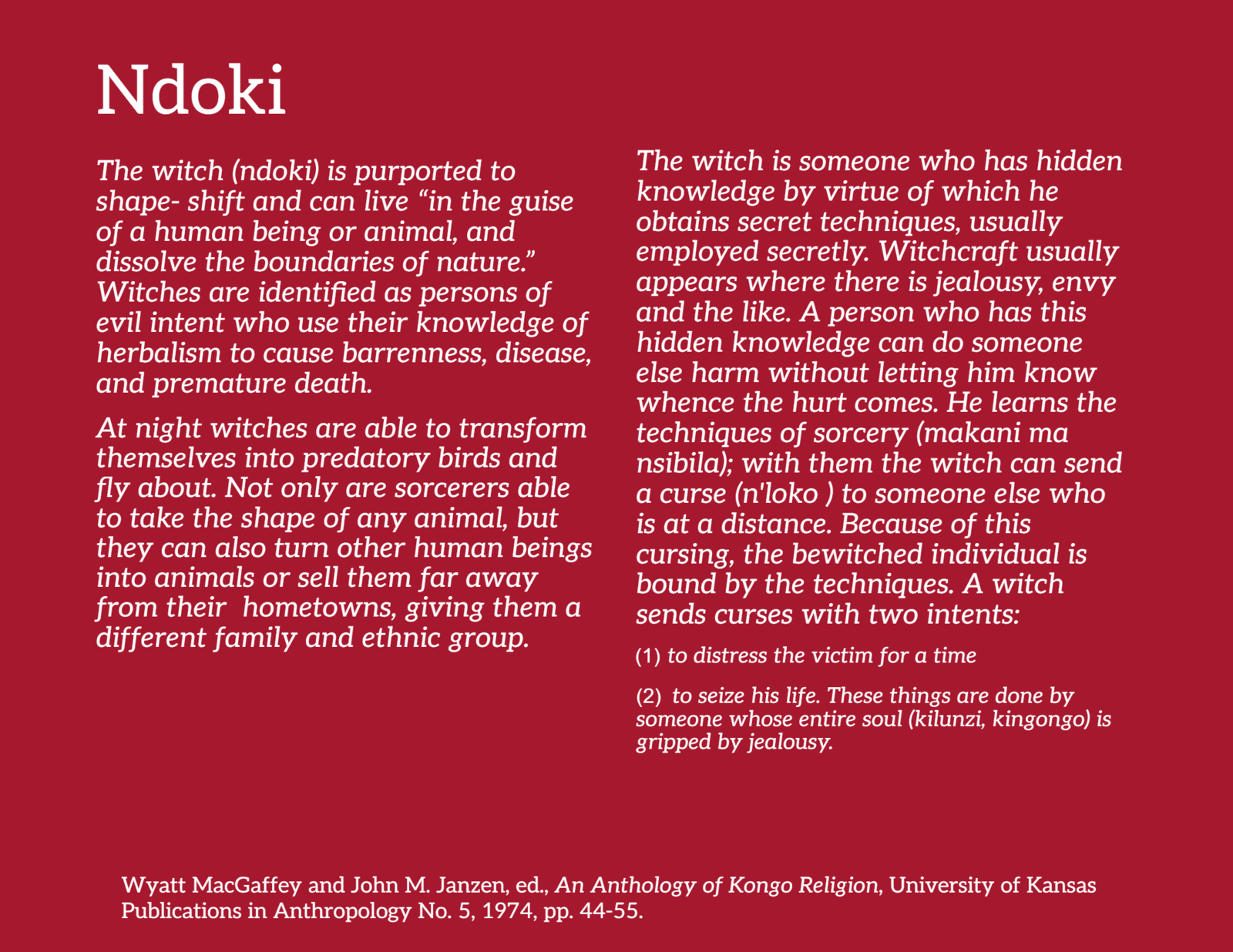

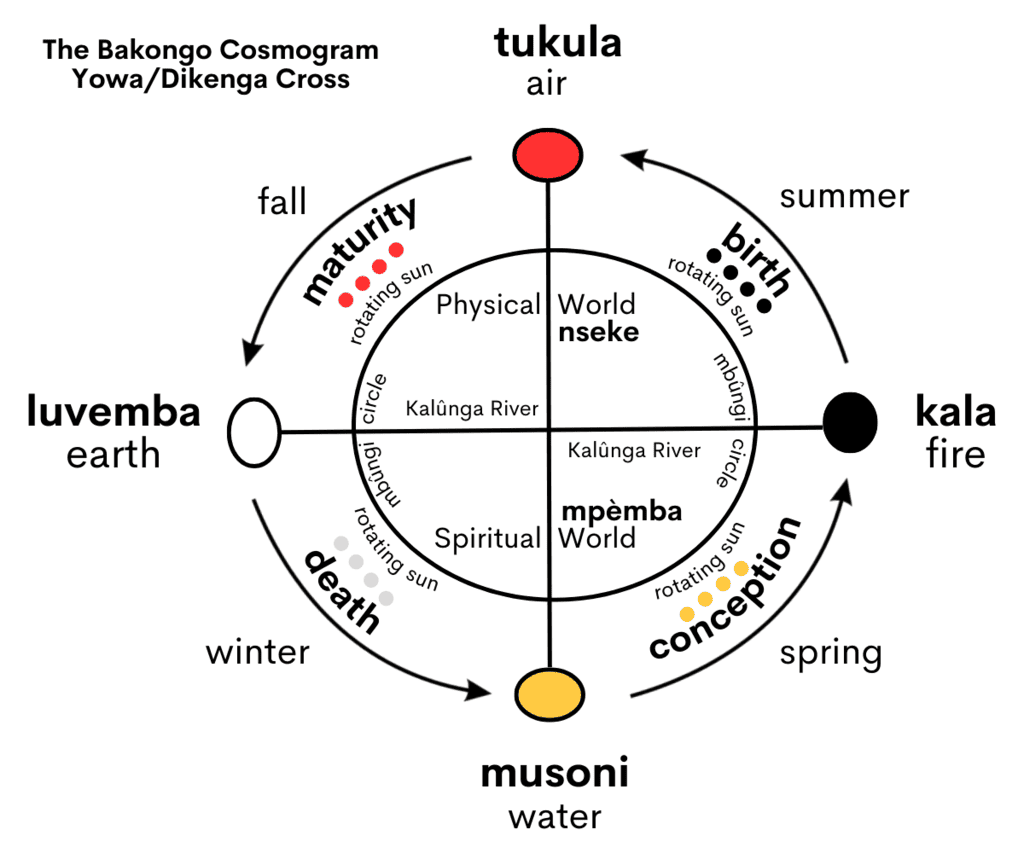

The homes of dignataries like the chief and the nganga would have been located at the four entrances to the village as the number four represented the four moments of the sun.

Huts were made out of baked clay, mud bricks, wood and grasses and sat on a foundation of stones. They would have been decorated with painted mats.

Life was dictated by the elements, the seasons and the cycle of the sun. At night the sun descended into the ancestral realm before re-emerging into the land of the living at sunrise. When a child was born it was thought that a living sun had risen into the upper world.

In January and September the God of Rain, Bunzi, brought some relief from the constant heat. Huts had sloped roofs to guard against the rain and the women would have hoed the fields into ridges to prepare for the rainy season.

The section of the river, upstream of a series of dramatic waterfalls, supplied the villagers with species of fish that no one else on earth would ever taste like the lionhead cichlid and spiny eel fish that inhabited the rapids and the irridescent tetra that preferred the murkier waters.

The spiney eel fish swam in the fast- flowing water, whilst the leopard lung-fish roamed the river bed hibernating in burrows in the dry season before re-emerging when the rains came. Villagers dug up lung-fish and kept them in their natural storage container until they were ready to eat them.

But fishing was no easy feat. The men would have to compete with the fish-eagle and risk becoming prey themselves if the carniverous man-sized tiger fish attacked. By comparison, hunting for goats or pigs may have seemed like the safer option.

If there was a big catch the women would have salted or smoked any surplus fish to use in a stew another day. A pestle and mortar would have been used to grind cassava into flour for the nfundi dumplings to dip in it. They might have grown yams or kola nuts too.it.

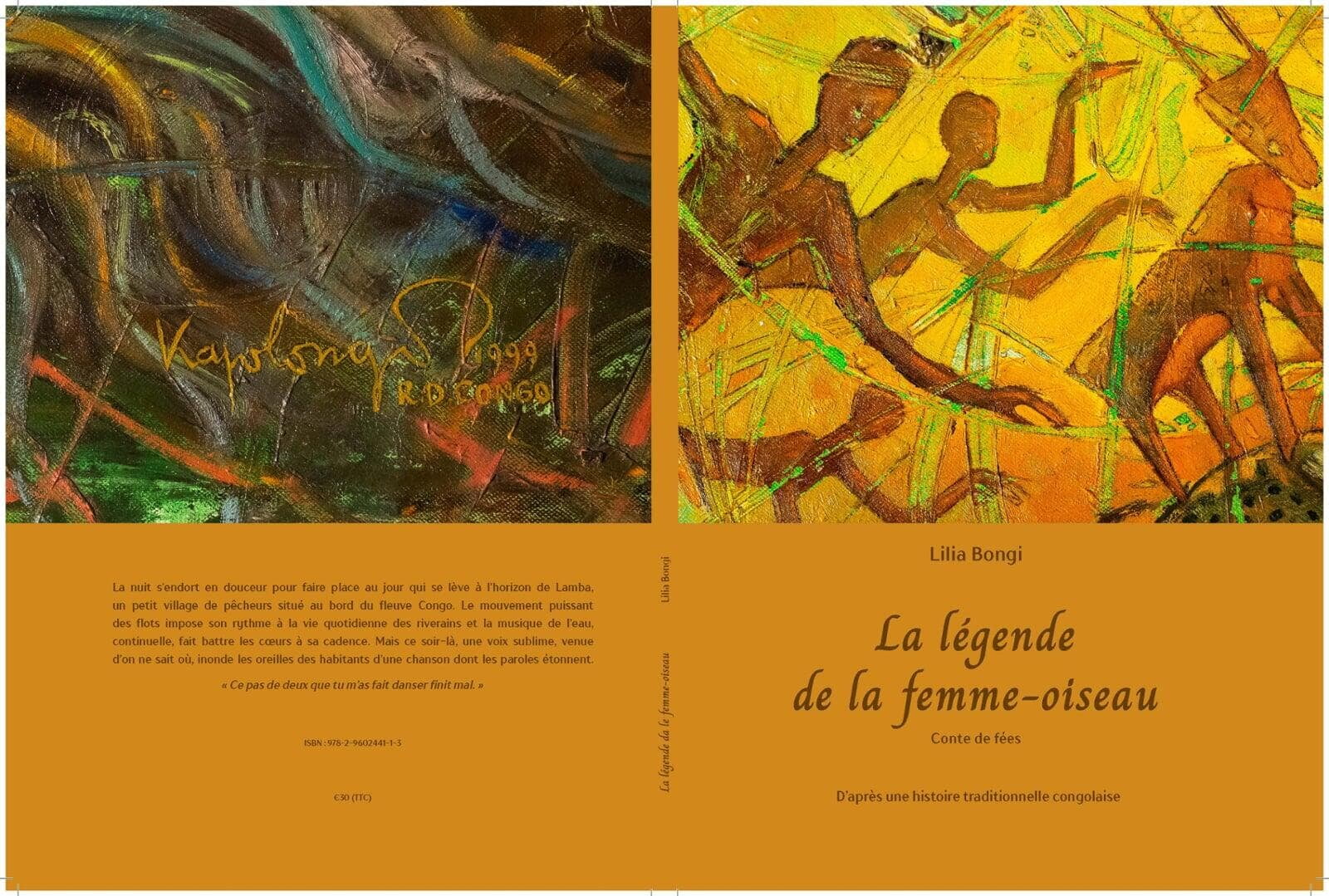

This would be washed down with palm wine. It was said that it was for the men to bring the food and the women to bring the wine. If the men didn’t bring the wine, the women would refuse to make the food.

Men would use a climbing loop to scale trees and tap their sap. Some of this wine might be sent to in an elaborate cup decorated with palm leaves ahead of an important discussion.

There would have been no waste. Raffia leaves would have been used to make fishing nets or baskets. The bark of the tree would have been used to make clothing, which in turn would have doubled as blankets in the evening. Palm oil would have been put to good use by the nganga in his ointments.

Although some individuals had a special status, the needs of the community as a whole were paramount. Land would have been held in common and harvests shared out equally. Any surplus would have been traded at markets, paid to the king in taxes or left as offerings to the ancestors. If one member of the community committed a crime, the whole village would be held responsible and might be collectively shunned or even enslaved.

History was passed down through folktales, song and dance. Animals represented particular human characteristics and fables served to impart a moral lesson. Mudfish were identified with royal women. Birds were portrayed as messengers, revealers of secrets or avengers of crime. Some tales would have been sung in the style of a birds like the yellow warbler.

Characters included cunning tricksters, man-eating water snakes, avenging hunters and envious wives. Victims often met their demise at the bottom of a hole, having been pushed by a wily adversary. They might then come back to life, sometimes in animal form. Stories would be told to captivated crowds in the village square. They were interactive and the would join in with singing at key points in the story.

Dance was another medium through which stories were told, but was also used to celebrate a plentiful harvest, honour new mothers or rejoice at the birth of twins. During the first stage of the dance the drum would have been played alongside the conflicting rhythm of the pestle and mortar. Then, the drummer would have launched into a continuous rhythm as the women rotated their hips.

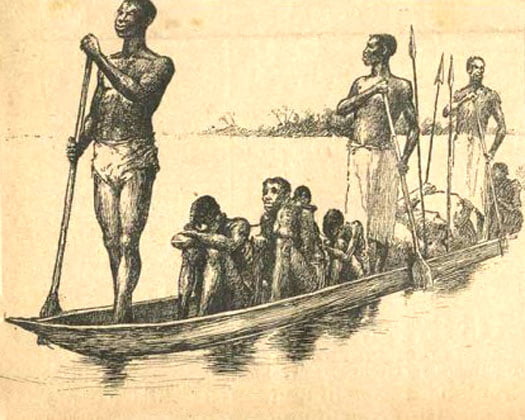

After decades of fighting between rival claimants to the throne villagers would have been traumatised and in a constant state of fear. Throughout the kingdom ordinary villagers and nobles alike were being taken prisoner. Some were forced to work for their captors but the majority were exported to Brazil or North Carolina as slaves.

Those who escaped this fate risked going hungry as armies pillaged their fields for food.

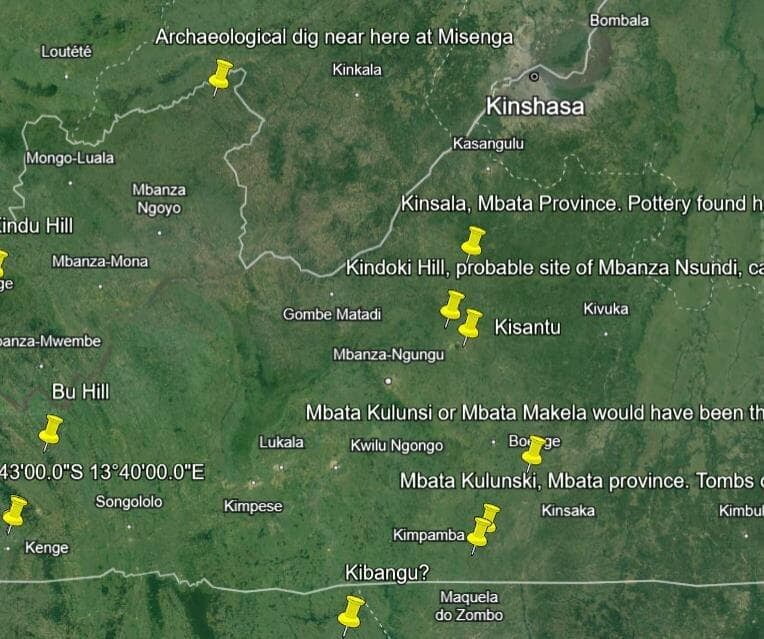

Villagers would have been ready to abandon their homes at a moment’s notice to take refuge in King João’s mountain stronghold at nearby Mbula.

Their traditions too were under attack. Christianity had been practised for six generations but Kongolese beliefs and customs had always coexisted alongside it. The Kongolese saw no contradiction between the two since there were many parallels. Even the Kongo cosmogram painted in the caves around Matadi was in the form of a cross and symbolised rebirth.

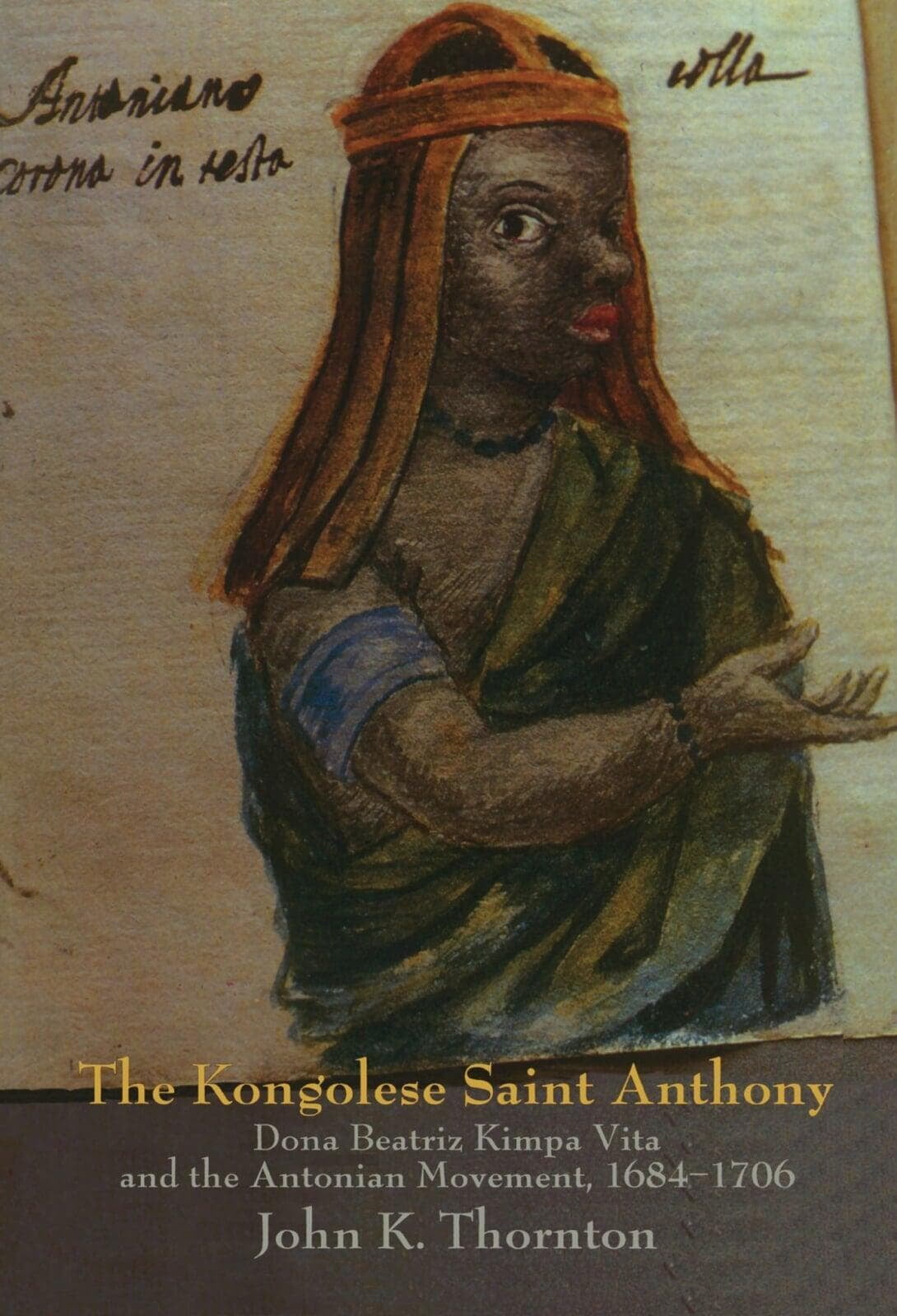

In the valley below King Pedro’s enclosure lived one of the initiates of such a community, a young Christian noble woman called Kimpa Vita. Her Christian name was Dona Beatriz but her Kongolese name, Kimpa Vita, suited her better. Kimpa derives from the Kikongo word for fable or legend, whilst Vita means ambush or war.

As a young woman Kimpa Vita had been initiated into the Kimpasa, a set of secret societies that used ritual and magic to resolve the social problems caused by the angry spirits. As a nganga marinda, a specialist in social issues, she saw the effect the conflict was having on ordinary people and was deeply affected by it.

In August 1704 Kimpa Vita fell gravely ill.

When she awoke from her fever one week later she reported that she had arisen from the dead and had been possessed by the spirit of Saint Anthony of Padua. Through him, God had given her a message: the Kingdom must be restored.

She climbed up the mountain to the fortress and demanded an audience with the King. In the name of St Anthony, she implored him to reoccupy the long-abandoned capital of São Salvador and reunite the kingdom for it was God’s will.

She stood before his throne and boldly demanded that he reoccupy the long-abandoned capital of São Salvador. When he ignored her pleas she told him that if he didn’t have what it took to restore the kingdom, she would do it herself.

She claimed that Jesus had been born in São Salvador and baptised in Kikondi, just a few miles from Lamba. She rejected the Christian cross, denounced images of white saints as false idols and rewrote the Salve Regina to reflect Kongolese beliefs. Like Kongolese religion, her new faith stressed the importance of intention in determining who was good and who was evil. She waged war on all forms of greed and jealousy which were considered the source of the malevolent powers of n’dokis.

As an effective infertility healer she was popular among women, since they lived in fear of being abandoned by their husbands. News of her miracles spread and her message of peace won her a huge following among villagers who had endured war, humiliation and fear for decades.

By November they had marched on the long-abandoned capital and reclaimed it in the name of Saint Anthony. Kimpa Vita took up residence in the cathedral and sent missionaries, known as Little Anthonys, to the provinces and to rival kingdoms.

Commoners and nobles alike flocked to her side, including the King’s own wife and one of the army commanders sent by him to reoccupy the city.

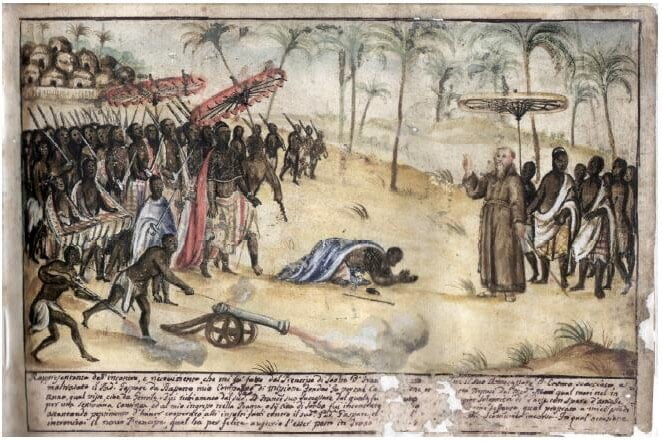

When the priests’ denouncements of the new religion and excommunication of its followers proved ineffective, King Pedro began to recognise the political threat Kimpa Vita’s movement represented. She was arrested and, at the urging of Father Lorenzo put on trial for heresy.

She received her death sentence in the King’s temporary capital in full view of the woodpile that had already been assembled by the crowd. The King and his Priest debated whether baby Antonio, who was still in his mother’s arms, should burned alongside her but ultimately spared his life. He was taken from her by church officials and would be baptised Jeronimo. His mother was beaten by a mob then dragged through the public square to the awaiting pyre.

A year later King Pedro IV marched on the capital. The remaining Antonians fled to Bula to seek the help of King João but were defeated soon after. Ultimately, King Pedro IV would reunify the Kingdom and stamp out Antonism, exporting 30,000 of his subjects as slaves in the process.

But Kimpa Vita’s ideas lingered in the villages of Africa and echoes of her resistance could still be heard centuries later in the defiant rallying cries of slaves from North Carolina to Haiti.